A. J. Philip

A. J. Philip

I asked the chairman of an institute why it lost its FCRA account. He told me that his name and the fact that he was from Kerala might have played their own roles. When he said this, I recalled RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat mentioning Kerala as a problematic place in his Vijayadashami Day speech at Nagpur.

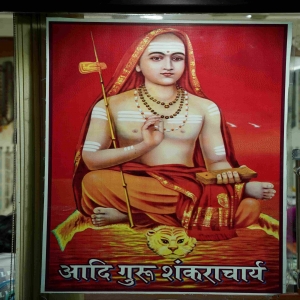

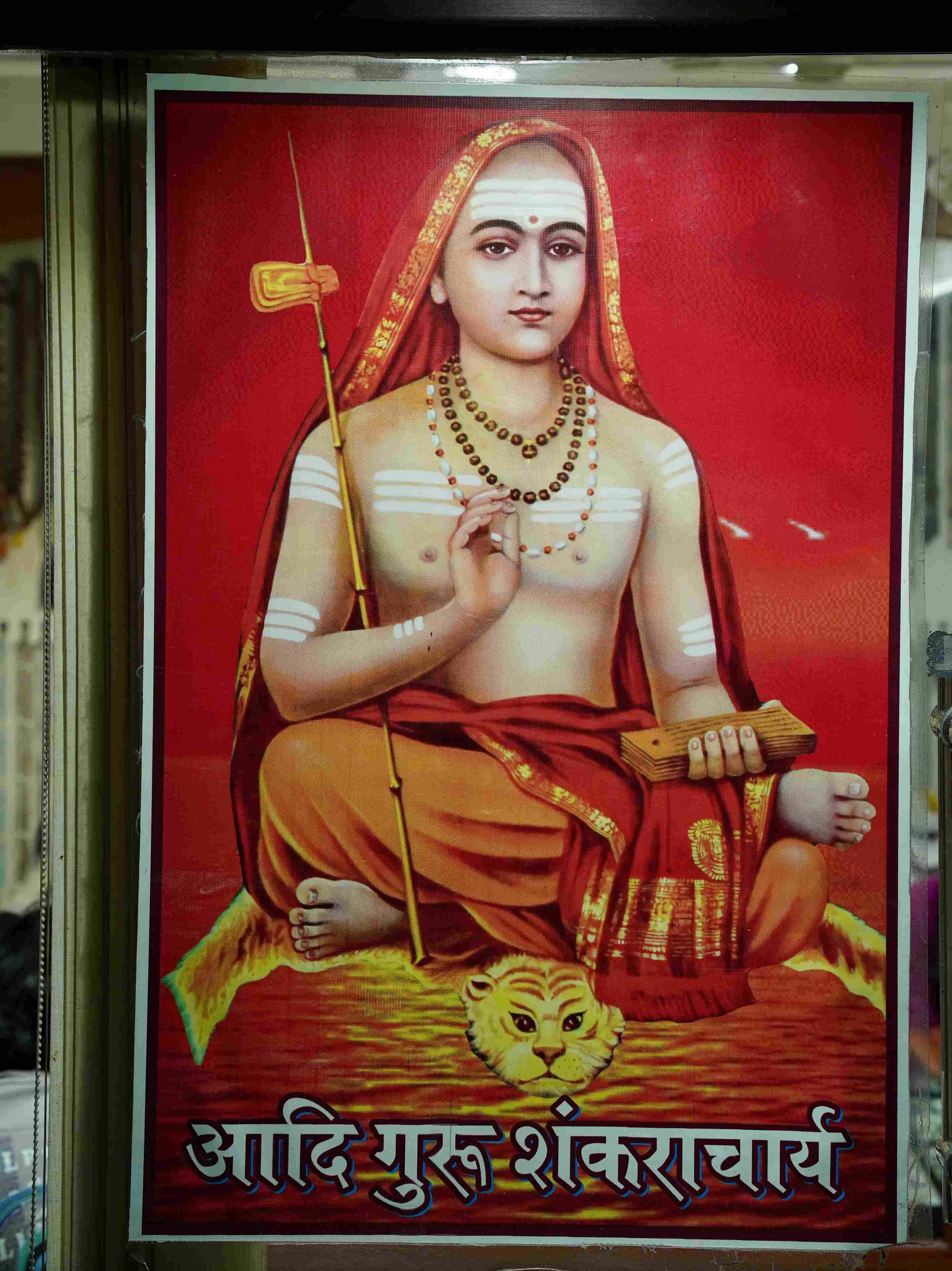

Earlier this week, during a visit to an Ashram in Rishikesh, I noticed a beautiful framed picture of Adi Shankara, who lived in the eighth century, at the entrance. As I moved ahead, I saw a depiction of Mahabali being deceived into giving away his land, which is Kerala.

As the story goes, Mahabali was a great ruler under whose reign nobody told lies, and everyone had their legitimate needs met. There was no conflict among the people. Mahabali's rule was ideal, and the people no longer aspired to go to heaven because Kerala itself had become a haven of prosperity.

Word reached the heavens that a little heaven existed on earth. Mahabali was no pushover, as he had acquired power through penance and was, therefore, unassailable. He was busy holding a Yaga, which would have made him almost invincible. However, Lord Vishnu decided to end Mahabali's rule by taking his fifth avatar as Vamana.

Vamana appeared as a dwarf-like Brahmin. When the pious Mahabali asked what gift the holy man desired, Vamana requested only as much land as he could cover in three steps. Mahabali, realising it was a trap, decided to grant the request.

The moment Mahabali asked the dwarfish supplicant to measure the three steps of land, Vamana assumed an unimaginable, cosmic size. He measured the entire universe in two steps. Then, he asked Mahabali where he should place his foot for the third step. Mahabali knelt and asked Vamana to place his foot on his head. He knew he would be pushed down to Patal, understood by many as hell.

Before Vamana placed his foot on Mahabali's head, the latter asked for a favour—to be allowed to visit his subjects once a year. His yearly visit is celebrated as Onam by Malayalis worldwide.

The Srimad Bhagavatam, which tells this story, describes Mahabali as a demon ruler but also as a popular, honest-to-the-core, brave person.

I always wondered where all the Rakshasas described in the sacred texts had disappeared. Was it because the wheatish-complexioned Aryans found the dark-hued Dravidians detestable and thus labelled them as demons? Even in the 21st century, matrimonial columns in newspapers and on matrimonial sites expect brides to be "fair and convent-educated."

Good governance was once synonymous with Kerala. That is precisely why the state is ahead on almost all social indices, such as women's education, literacy, life expectancy, and infant mortality. It is often claimed that Gujarat has achieved greater economic growth than Kerala, but this is questionable.

In fact, Kerala's minimum wages are higher than Gujarat's, and it attracts a large number of workers from states like Bihar, West Bengal, and the Northeast. The inflow from Tamil Nadu has stopped as the state is developing at a faster pace. Incidentally, the RSS chief grouped Tamil Nadu with Kerala in his speech.

This is likely because his party couldn't win a single seat in this year's Lok Sabha elections, despite the Prime Minister bringing a plane-load of priests from Tamil Nadu for the "consecration" of the Sengol in the new hexagonal Parliament building, which many say resembles a coffin.

I was at the Ashram to watch the evening Aarati. It was my second time witnessing it on the banks of the Ganga. There are several spots along the river where Aarati is held. The last time I visited a different one, where a few handsome men made quite a show of the heavy lamps they held. It was a thrilling experience, which is why I wanted to see it again this time.

Unfortunately, by the time we reached the venue, Aarati had already begun. Of course, the place was crowded with well-heeled people, including quite a few foreigners. A Catholic priest who accompanied me lamented missing a discourse by a foreign lady before the Aarati. He was ecstatic as he described the lady and her manner of speaking. I rely on those who heard her to make the following comments.

She has a good command of both English and Hindi, sticks to her script like a leech, and speaks in a measured tone without hyperbole. Her listeners are highly impressed, to the point that one priest remarked, "Any foreigner who listens to her will instantly fall for her teaching."

As he said this, I remembered how difficult it has become for the Mar Thoma Syrian Church, to which I belong, to bring a theologian from the West to speak at the 130-year-old Maramon Convention held every February. Our nation fears foreign missionaries but welcomes them if they wear ochre robes and a rudraksha chain and call themselves Sanatanis, if not Hindus.

No, I am not complaining, as there are enough Christians in India who can speak the word of God without needing foreigners who may not even understand the significance of, say, a taali that every Christian married woman in India wears. To them, it's all about the wedding ring.

After welcoming the people who had gathered to witness the Aarati, the lady would tell them that a dip in the sacred Ganga would absolve their ancestors of the sins they committed, especially if they had come to Rishikesh to pray for their souls.

Unlike Christianity, certainty guides Hinduism and Islam. If a Muslim practices what the religion prescribes—praying five times a day, practising charity as required, and visiting Mecca at least once in life—he is assured a place in heaven. Similarly, for the Hindu, taking a bath in the Ganga, performing certain mandatory rituals, and making substantial offerings to gods and goddesses will see them through the cycles of birth.

In the case of Christianity, there is no such certainty about reaching the other shore. For instance, the Bible says: "Then Jesus said to His disciples, 'Assuredly, I say to you that it is hard for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. And again I say to you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God."

The poor get precedence in God's eyes, as He valued the widow's mite more. In fact, Jesus commands: "Sell everything you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me." Easier said than done!

In Christianity, discipleship comes with a price. Of the 12 disciples Jesus had, only John died a natural death from old age. He played a significant role in the early Christian church, particularly in Ephesus, where he is said to have lived and ministered until his death. All others, including St. Thomas, who came to India, met violent deaths. Certainty eludes the Christian, for he cannot confidently say that he will sit beside Jesus.

No wonder people in the West are moving away from Christianity, drawn instead to Oriental ritualism, as seen in the Aarati. Kerala has played a significant role in this shift.

How many know that most, if not all, Hindu goddesses were draped in saris by a Malayali—artist Raja Ravi Varma? It's incidental that they also have a Malayali look, resembling women from rich, aristocratic Hindu families. Yet, despite the elegance of the sari, it is not the national dress in many states of India.

Another Keralite made an even greater contribution to Hinduism—Adi Shankara, born in Kalady, near Aluva in Kerala. He was the first to visit places like Rishikesh, in what is now Uttarakhand, but he didn't stop there. He travelled further to Badrinath, where the temple still has a Malayali Namboothiri as its priest.

I first read about Shankara in Dr S Radhakrishnan's Indian Philosophy, a two-volume work. I was so pleased with it, even though I didn't understand many of the religious concepts, that I even considered taking philosophy as my major for my BA. Alas, none of the colleges near Pathanamthitta offered such a course.

Dr Radhakrishnan compared Shankara to Saint Augustine, who developed Plato's idea of the rational soul into a Christian view, wherein humans are essentially souls using their bodies to achieve spiritual ends. Augustine also helped formulate the doctrine of original sin and made significant contributions to the just war theory.

Shankara, in contrast, embarked on the Digvijay Yatra, establishing four mutts in the four cardinal directions—Badrinath in the north, Dwarka in the west, Jagannath Puri in the east, and Sringeri in the south. Some claim that Kanchi is his original mutt, though others dispute this.

It's believed that Shankara drove Buddhism out of India, where it had been the dominant religion in many regions. India as we know it, or Bharat, was formed by integrating over 500 princely states into the Indian Union by VP Menon, the right-hand man of Sardar Patel.

Uttarakhand is seeing significant developments, including an underground railway project. Once completed, one could travel by train from Kanyakumari to Badrinath. Credit must go to Modi, as he seems more interested in religion than in education.

A friend was scandalised when I told him that I had a boiled egg for breakfast. He wondered how I could have it in Rishikesh. I checked and found that eggs are easily available, though meat, poultry, and fish are forbidden. Of course, those in Rishikesh with a craving for tandoori chicken or rogan ghosht need only travel to the point where Rishikesh ends, and Dehradun begins. Interestingly, Rishikesh is closer to the Dehradun airport than downtown Dehradun.

After the Aarati, it was time to return. Since tea time is anytime, we decided to try the Chotiwala Restaurant. I noticed it last time as well. Its main attraction is a pot-bellied man sitting on a pedestal at the entrance, supposedly a Brahmin. While all others received a bow, he gave me a full namaste—perhaps because I had a camera hanging from my neck. Chotiwala means the one with a tuft of hair—Brahmin. I felt pity for him, as he must sit like a mannequin all day to earn a living.

We returned via the Ram Jhoola. I had crossed the river last year using the Lakshman Jhoola, which was built by the British with substantial financial contributions from Hindus. Legend has it that when Ram, Lakshman, and Sita reached there, they wanted to cross the river. Lakshman built a bridge with arrows. There is a temple there to commemorate the event. Otherwise, Lakshman is not a deity except when in the company of his elder brother and sister-in-law.

Rishikesh possesses an undeniable charm that lingers long after you have left its sacred banks. The confluence of spirituality, mythology, and scenic beauty weaves an enchanting tapestry that calls you back again and again.

Whether it's the soul-stirring Ganga Aarati, the timeless stories of gods and demons, or the serene hum of the Ashrams, Rishikesh remains a place where the ancient and the present coexist in perfect harmony—drawing pilgrims, seekers, and curious souls alike to return and rediscover its magic.