.jpg) Sacaria Joseph

Sacaria Joseph

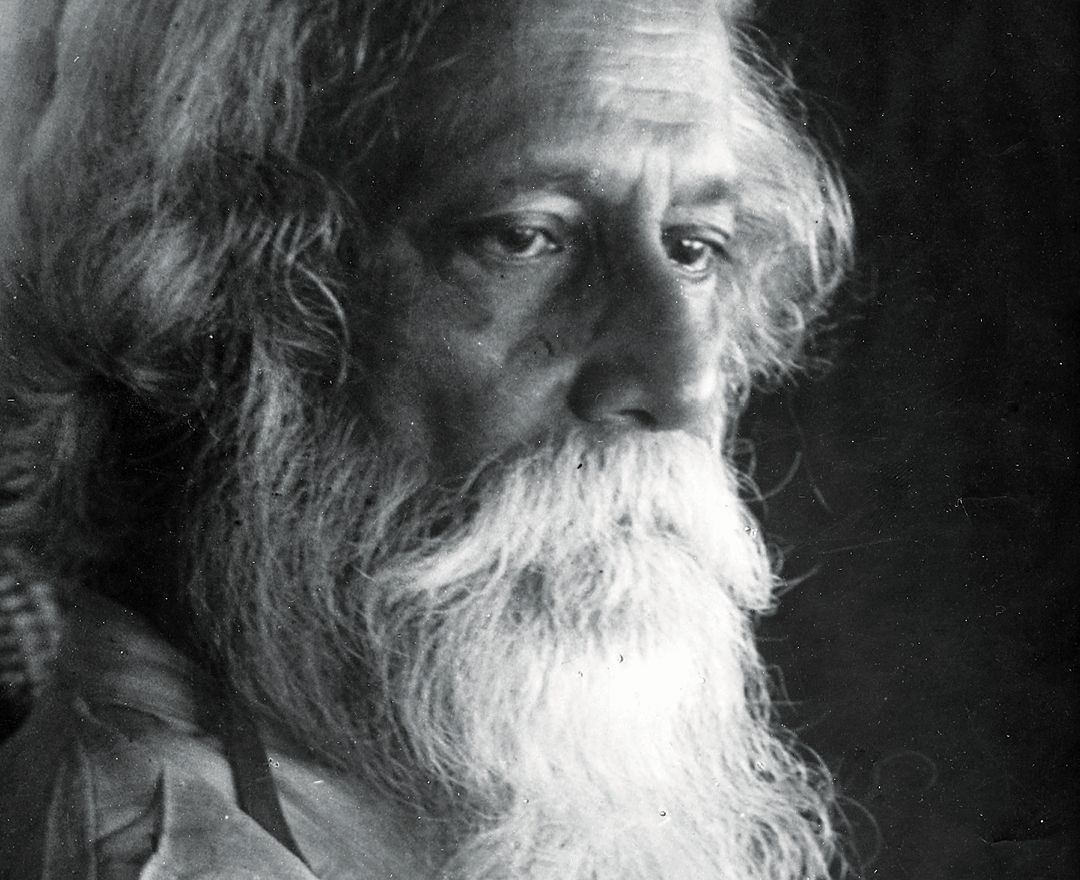

In the early twentieth century, as militant nationalism swept across India, Rabindranath Tagore emerged as a radical departure from the dominant nationalist ideologies. His approach, grounded in humanism and a profound sense of global unity, challenged the very core of the militant nationalism that gripped the nation.

While his contemporaries championed a narrow, parochial nationalism, Tagore envisioned a nation defined not by its boundaries or its power but by its commitment to universal values. His poetry and philosophy offered a profound critique of militant nationalism's destructive tendencies, advocating instead for a nation that embraced diversity, intellectual freedom, and spiritual enlightenment.

In his celebrated poem "Where the Mind is Without Fear," Tagore articulates an idealistic yet enduring prayer for his nation. He imagines a utopian ideal as a physical place where the mind is free from fear, knowledge is accessible, and the world is not fractured by narrow domestic walls. This timeless plea, part of his Nobel-winning Gitanjali collection, reflects Tagore's yearning for an intellectual and spiritual awakening in India, where truth, reason, and progress reign supreme. It offers a fundamentally new approach to nationalism, envisioning a nation defined not by its boundaries or power but by its commitment to universal values.

Tagore's nationalism was far more than a mere call for political liberation. His ideas sought to awaken a deeper form of freedom – freedom from ignorance, orthodoxy, and hatred. He feared that the fervour of nationalism, if not checked by a broader humanitarian spirit, would degrade into the very oppression it sought to dismantle. Therefore, in one of his letters to his friend, AM Bose, in 1908, he wrote, "Patriotism cannot be our final spiritual shelter; my refuge is humanity. I will not buy glass for the price of diamonds, and I will never allow patriotism to triumph over humanity as long as I live." For Tagore, the nation was not an end but a means toward a greater unity that embraced all of humanity.

Tagore's scepticism toward militant nationalism intensified during the turbulent events of Bengal's partition in 1905 and the ensuing Swadeshi movement. The violence that erupted during this period—often carried out in the name of patriotism – deeply unsettled him. While many saw the burning of foreign goods and the use of force against British colonial powers as acts of patriotic duty, Tagore perceived a disturbing trend. He saw nationalism transforming into a divisive tool that fostered fragmentation and conflict rather than promoting unity and collective growth.

The tragic episode of Khudiram Bose, a young revolutionary executed for killing two British civilians in a botched assassination attempt, served as a turning point for Tagore. While the Bengali youth lauded Khudiram as a hero, Tagore withdrew from the nationalist movement, disillusioned by its increasingly violent trajectory. His ideals of non-violence and inclusivity starkly contrasted with the bloodshed that marked the era's nationalist fervour.

Tagore also recognised the hypocrisy within the economic dimensions of the nationalist agenda. The Swadeshi movement, which encouraged the burning of foreign goods and the exclusive use of indigenous products, had unintended consequences, particularly for the poor in Bengal. Locally made goods were often more expensive than imported ones, forcing the impoverished to shoulder the burden of nationalist economic policies. Tagore emphasised in his critique that the pursuit of dignity and self-respect should never come at the expense of oppressing one's own people.

While Tagore firmly believed in India's right to independence, he rejected the idea that true liberation could be achieved through blind adherence to symbols like the charka (spinning wheel), a central tenet of Gandhi's philosophy. Tagore understood that India's freedom would not come through isolation but through education and meaningful intellectual engagement with the wider world. In contrast to Gandhi's emphasis on self-sufficiency and traditional crafts, Tagore advocated for a path to independence that embraced self-reliance and openness to global ideas. This difference in perspective highlights the contrasting approaches of these two influential figures in the Indian independence movement.

At a time when the nationalist movement was advocating for a wholesale rejection of Western ideas and influence, Tagore urged India to remain open to progressive thought from all cultures. He envisioned a union between East and West, where both could meet as equal partners in a creative dialogue. Tagore's critique of the West was sharp – he condemned its obsession with materialism and militarism but never gave up hope for a synthesis between Eastern spirituality and Western scientific and intellectual advancements.

His advocacy for inter-civilisational dialogue was grounded in his belief that India's isolation from the rest of the world would only lead to stagnation. In his essay, East and West, Tagore lamented, "The West comes to us, not with the imagination and sympathy that create and unite, but with a shock of passion – passion for power and wealth." Yet, he still believed that there was much India could learn from the West, just as the West could benefit from India's spiritual wisdom.

Tagore's novel Ghare Baire (The Home and the World) sharply critiques nationalist zeal. The story contrasts two men – Nikhil, a social reformer who believes in women's liberation and rejects aggressive nationalism, and Sandip, a fervent nationalist who preaches that devotion to the country must surpass all other values, including humanity. The novel's protagonist, Bimala, is initially enamoured by Sandip's charismatic nationalism, only to later recognise the destructiveness of his ideology. In the end, it is Nikhil – the man committed to humanitarian values – who risks his life to protect victims of sectarian violence. At the same time, Sandip flees from the chaos he helped incite.

The novel underscores Tagore's warning – when patriotism becomes idolatrous, it inevitably leads to violence and oppression. As Nikhil says in the novel, "I am willing … to serve my country; but my worship I reserve for right which is far greater than my country. To worship my country as a god is to bring a curse upon it." For Tagore, the true enemy of a nation was not a foreign power but the internal divisions and moral failings that patriotism, if unchecked, could exacerbate.

In his prayer for India, Tagore did not envision a country isolated from the rest of the world. His call for a "heaven of freedom" was not limited to political emancipation but encompassed a broader vision of a free, just, and intellectually engaged society. In Where the Mind is Without Fear, Tagore asks for a country where the mind is fearless, where knowledge is free, and where reason and truth guide the actions of its citizens.

Tagore's nationalism was thus not about dominance, exclusion, or even self-sufficiency in the narrow sense. It was a call for an enlightened and inclusive India that would be a beacon to the world, not because of its power but because of its commitment to human dignity, intellectual freedom, and moral righteousness.

In today's world, where nationalism often devolves into xenophobia and sectarianism, Tagore's vision remains as relevant as ever. His call for a balanced, humane, and global form of nationalism reminds us that true patriotism must be grounded in respect for humanity. In Tagore's ideal, India would not just be free – it would be a light for the world.