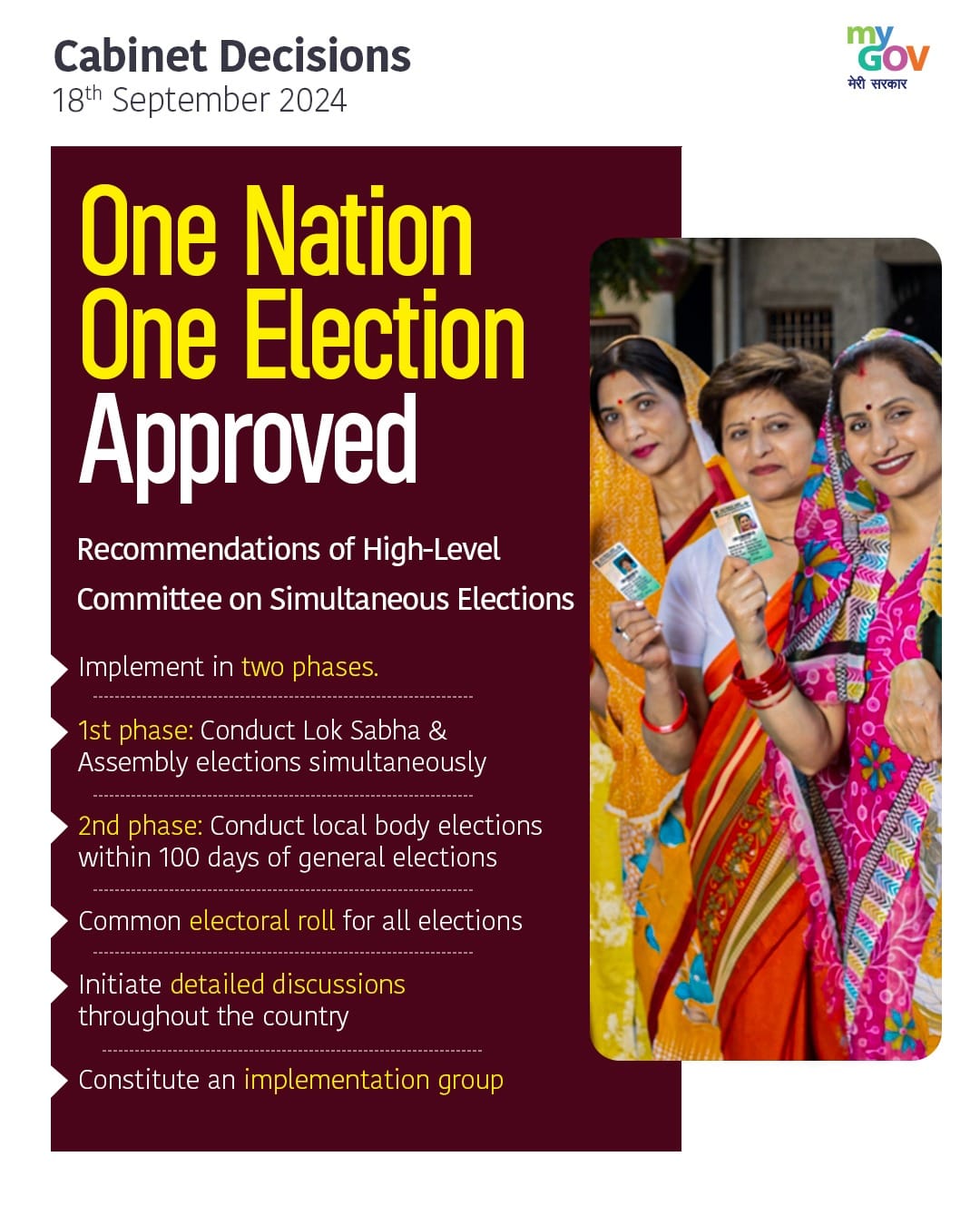

The 'One Nation, One Election' proposal has sparked a significant debate on modern Indian politics once again, following the Union Cabinet's recent decision to approve it. The government is trying to take India back to a pre-1967 electoral practice with a two-phase election process that covers Lok Sabha and state assembly elections, followed by local body elections within 100 days. A committee led by former President Ram Nath Kovind has recommended simultaneous elections, citing their promise of a more efficient and less disruptive electoral cycle as well as advantages for administration, the economy, and governance. However, there are risks and difficulties associated with this bold suggestion. The idea has gained a lot of support from people who emphasise the need for cost-cutting and effective governance. But it has also come under fire from some quarters. They fear it could upset the political balance between national and regional parties and threaten India's federal structure.

The idea of coordinating the state and federal electoral cycles has been put forth as a solution to India's frequent elections. Every few months, a state in the nation holds elections. This involves many administrative and financial responsibilities in addition to the imposition of the Model Code of Conduct (MCC). MCC limits the government's capacity to announce or introduce new initiatives during election season. In order to win over the electorate, governments are compelled to turn to populist politics, which is why proponents of simultaneous elections contend that the current system produces a situation of almost constant electioneering. They contend that in addition to delaying significant policy initiatives, this never-ending electoral cycle results in an ineffective use of resources.

A synchronised election schedule would lower administrative costs and free up ruling parties to concentrate on governance rather than elections. It may also lessen the MCC's frequent imposition, according to the Kovind committee's recommendation, which considers these concerns. Elections are unquestionably an expensive event. The government spent thousands of crores for the 2024 Lok Sabha elections alone. State elections also require significant time, money, personnel, and logistical resources. Theoretically, combining these elections into a single, significant event would result in significant cost savings, a reduction in the need for personnel and administration, and the release of funds for development. Additionally, the MCC's disruption of governance and economic activity would be reduced by holding elections at regular intervals, which might permit the continuous flow of policy decisions.

Proponents of One Nation, One Election contend that it could lessen the threat of black money in elections in addition to these benefits to the economy and governance. Political parties and candidates must continuously raise money for elections, which frequently comes from unreported sources. Reducing the number of elections would help create a more transparent and orderly electoral system by limiting these opportunities. Election fatigue would be lessened, which would increase voter turnout and encourage more political engagement, which is another advantage that is frequently mentioned. Voter apathy can occasionally develop from multiple elections in a short period of time, especially in local body elections, as voters become weary of frequent elections. Since there would only be one Election every five years under a synchronised election system, voters might become more engaged.

Notwithstanding these advantages, there are numerous obstacles in the way of holding simultaneous elections on a practical and constitutional level. The requirement for significant constitutional amendments is the most pressing barrier. The government would have to amend a number of constitutional provisions, including Articles 83, 85, 172, and 356. These articles address the duration and dissolution of the Lok Sabha and state legislature in order to implement this proposal. There would also need to be a significant overhaul of the 1951 Representation of the People Act, which governs election procedures. It is not an easy task. The ratification of constitutional amendments by the majority of state legislatures and a two-thirds majority in both houses of Parliament are prerequisites. Such broad support seems unlikely to be obtained in the current political climate, where consensus on any major issue is elusive. Moreover, imposing these amendments without conducting extensive consultations or reaching a consensus runs the risk of facing strong political and constitutional opposition.

Beyond the obstacles posed by law and the constitution, the practical and political ramifications of holding simultaneous elections present the bigger obstacles. Because of its federal design, India's states have distinct political systems and schedules. Political unrest or other causes may cause state governments to fall before their entire tenure in certain circumstances. So, the question is raised: What would happen if a state government were to fall before the following simultaneous Election? Would the state continue to be governed by the President's Rule until the following election cycle, thereby possibly depriving the people of their right to vote for a number of years? Would it be necessary to reschedule the entire national election cycle, which would cause the kind of disturbance that the One Nation, One Election plan aims to prevent? The policy's supporters have not yet provided a satisfactory response to these important concerns.

Furthermore, the proposal poses significant questions regarding the distribution of power between national and regional parties. Voters may be more swayed by the national political narrative when they simultaneously cast their ballots for both their state assembly and the Lok Sabha. This could easily lead to national issues taking precedence over local ones. As a result, regional parties that concentrate on local issues may lose out to national parties like the Congress and BJP, which have the organisational clout and financial means to run in elections across the nation. This could diminish the political representation of regional voices and undermine the federal character of the polity in the country. Regional identities and issues are important in state elections as diverse as India.

Simultaneous elections have the potential to not only weaken regional parties but also put more pressure on political parties to run coordinated campaigns across the nation. This might cause political discourse to become unhealthyly centralised, marginalising local issues in favour of national ones. The political playing field would be further skewed in favour of larger, better-funded national parties since smaller parties would not have the organisational strength or resources to run for office on multiple fronts at once. Opponents of this suggestion worry that the plan may worsen power concentration. It may also undermine India's federal democracy, despite supporters' claims that it will improve governance by establishing more stable governments at both the state and central levels.

The effect of simultaneous elections on governance is another important issue. There is a counterargument to the claim that holding all elections at once would lessen the frequency with which the MCC is imposed. They also argue that it may free up governments to concentrate on crafting policies without being sidetracked by elections. Elections for the Lok Sabha, state assemblies, and local bodies would all need to be coordinated over a 100-day period, which would mean a longer MCC period if they were held concurrently. Compared to the current system, in which the MCC is imposed one state at a time, this could result in governance being paralysed for an extended period of time. During this prolonged MCC period, the delay in announcing policies or starting new initiatives may negate some of the benefits that simultaneous elections are supposed to bring to governance.

Moreover, it is important to recognise the enormous logistical difficulties involved in conducting simultaneous elections throughout India. The Election Commission would have to drastically expand its operations in order to hold simultaneous elections at the federal, state, and local levels. The Election Commission already has a difficult time holding elections at different times. This would necessitate not only a massive increase in resources, such as more polling places, personnel, VVPATs, and electronic voting machines (EVMs) but also a major improvement in the Election Commission's logistical capabilities. The one-time cost of getting ready for synchronised elections would be very high. There is also no guarantee that the endeavour would be successful, even though the long-term savings might make the initial resource outlay justified.

The question of why the government is so eager to move this proposal through at this time emerges in light of these obstacles. One explanation is that the ruling party may benefit politically from simultaneous elections. Reducing the need for repeated campaigning and mobilisation efforts, the government can concentrate all of its resources and campaign machinery on a single electoral cycle by combining the elections into one big event. Additionally, as previously indicated, given Prime Minister Narendra Modi's popularity across the country, national issues are likely to dominate the political narrative during a synchronised election that could be advantageous to the BJP. The ruling party may be able to silence critics at the state level by drawing voters' attention to national issues, securing both the central and state governments in one fell swoop.

But there is a big price to pay for this political advantage. The government might gain in the short run, but there is much less certainty about how simultaneous elections will affect India's democracy in the long run. The nation's democracy is seriously threatened by the possible demise of regional parties, the dissolution of India's federal system, and the concentration of political power. Moreover, the implementation of this proposal faces both logistical and constitutional challenges, raising doubts about its viability despite the claims made by its supporters. Despite its flaws, India's electoral system has developed over time to take into account the nation's great diversity and intricate political environment. There is a chance that attempting to impose a one-size-fits-all solution, such as simultaneous elections, will backfire and weaken the very democracy that it is meant to uphold.