.png) Dr. Mathew Paikada

Dr. Mathew Paikada

The third encyclical of Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti (FT), is a Franciscan encyclical in two ways. First, both in the introduction and in the conclusion, the Pope acknowledges that he was inspired by St Francis of Assisi to write this encyclical on the theme “(global) human fraternity and social friendship”.

Second, the content, the accent and the style of the encyclical are typically Franciscan (by way of both the Assisian St. Francis and the Bergoglio Pope Francis), even though explicit bibliographical references are minimum in the footnotes. (The encyclical with 287 paragraphs has already 288 footnotes!)

The unique Franciscan touch is clear when we compare the style and content of the first encyclical of Pope Francis, Lumen Fidei of July 2013, the draft of which was already prepared by Pope Benedict XVI, who resigned abruptly due to ill health, and was completed by Pope Francis. The apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium of Pope Francis in the same year showed the change of style and perspective.

The title of the present encyclical, Fratelli Tutti (All brothers and sisters), comes from the Admonitions 6 and 25 of St. Francis, “Blessed [is] that friar who loves his brother as much when he is sick and can be of no use to him as when he is well and can be of use to him. Blessed [is] that friar who loves and respects his brother as much when he is absent as when he is present” (Adm. 25).

Covid-19 is not the immediate context of the encyclical. The Pope himself points out that the pandemic broke out unexpectedly when he was already at work with the new encyclical. In two ways the encyclical continues programmatically the main focus of the ministry of Pope Francis.

First of all, the thought of Laudato Si (2015), the second encyclical of Pope Francis, which too was inspired by St. Francis of Assisi, is taken up and developed further. The theme, ‘earth is the common home for the whole of humanity,’ is developed to ‘the whole humanity is a single global fraternity in solidarity and friendship’ with mutual responsibility and accountability.

Secondly, the theme of inter-religious harmony and cooperation for peace and progress of the whole humanity, which was discussed between Pope Francis and the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, Ahmed al-Tayeb, in Abu Dhabi in 2019, is taken up again.

The meeting between the two religious heads, with the signing of a common declaration and a united appeal to humanity for “World Peace and Living Together” was held to commemorate the eighth centenary of the unusual historical meeting between St. Francis of Assisi and Sultan Malik al-Kamil of Egypt in Damietta on the delta of the Nile River, at the height of the fifth crusade in 1219.

The Pope wanted to bring to the attention of the whole world the fruit of their discussion as well as their common appeal to the entire humanity and the warm fraternal atmosphere of dialogue and cooperation for peace. The leaders of the most populous religions have a grave responsibility to join hands to ensure peace and progress of all through universal brotherhood.

The present encyclical of Pope Francis addressed to all people of goodwill has to be seen in this context. This is a social encyclical in the great tradition of Popes Leo XIII, Paul VI, and John Paul II, challenging, admonishing and pushing a new hope to the forefront.

Let us take a glance at the meeting between St. Francis and the Sultan of Egypt Malik al-Kamil. Francis had made two earlier attempts to preach to the Muslims in 1212 and 1213 and only the third attempt in 1219 succeeded.

The Spanish Cardinal Pelagius was the leader of the Crusaders and Sultan al-Kamil was leading the Saracens (Muslims) and the atmosphere was really tense. The Sultan had made an appeal for truce by offering to hand over the important holy places to the Christians and for a pact of non-aggression from the part of the Crusaders for the next 30 years. But it was rejected by the Cardinal as they were looking for a complete victory over the Muslims. Francis was shocked and distressed by the unchristian manners of the Crusaders.

The Muslims were called ‘cruel treacherous blasphemers’ by the Christians and they in turn were considered ‘belligerent idol worshippers’ by the Muslims. However, Francis appealed to give peace a chance, but the call fell on deaf ears. In the heavy fight that followed, the Crusaders had to suffer heavy loss. It was at this time that Francis with the permission of the Cardinal went to meet the Sultan personally, accompanied by Br. Illuminato (the interpreter).

Francis was surprised not only by the very fraternal welcome that he received, but also by their desire to listen to him. He was overwhelmed by the strict observance of their daily prayer and piety. He did not experience any hatred, prejudice or animosity at the court of the Sultan. On the contrary, he was welcomed with openness, hospitality and friendship. On his departure he was generously gifted and was guaranteed safe return.

This encounter has special relevance for our times, especially when some sort of ‘islamophobia’ is poisoning the peaceful atmosphere in many countries. Certainly there have been inhuman cruelties and persecutions perpetrated by some radical sections of Islamic fanatics in many countries.

Extremists and fanatics are found in every religion; however, it is the duty of every sane person to prevent them from carrying the day. After his return from Damietta, Francis did not hesitate to execute various good religious practices he found in the palace of the Sultan. Since he was impressed by the regular prayer at fixed times during the day, he wrote to the Rulers of People: “See to it that God is held in great reverence among your subjects; every evening, at a signal given by a herald or in some other way, praise and thanks should be given to the Lord God almighty by all the people”.

He took pains to initiate the custom of saying the prayer “Angelus” three times a day. Probably it is after his rendezvous with the Sultan that he introduced Chapter 16, or at least part of it, into his Earlier Rule (not approved) under the title: ‘Missionaries among the Saracens and other Unbelievers’.

In this chapter he presents a new way of evangelisation before stating the usual method of preaching and baptizing, viz. “to avoid quarrels or disputes and be subject to every human creature for God’s sake (I Pet 2:13), so bearing witness to the fact that they are Christians”. Many authors have been adding dubious reports about his ardent desire for martyrdom and his rejoicing at the news of the martyrdom of his brothers in Morocco.

Jan Hoeberichts, who did praiseworthy research on ‘Francis and Islam’ comes to the conclusion that “Francis’ mission is, first of all, to be seen as a peace-mission which emphasized not so much the proclamation or the preaching of the Gospel, but the ‘doing’ of it”. (Francis and the Sultan: Men of Peace, Delhi, 2018, p.27).

Pope Francis writes: “We are impressed that some eight hundred years ago Saint Francis urged that all forms of hostility or conflict be avoided and that a humble and fraternal ‘subjection’ be shown to those who did not share his faith” (FT 3).

In his introduction, Pope Francis writes about the situation of Assisi at the time of Francis: “In the world of that time, bristling with watchtowers and defensive walls, cities were a theatre of brutal wars between powerful families, even as poverty was spreading through the countryside. Yet there Francis was able to welcome true peace into his heart and free himself of the desire to wield power over others. He became one of the poor and sought to live in harmony with all. Francis has inspired these pages” (FT 4).

He sees a parallel to our times when he writes: “…we encounter the temptation to build a culture of walls, to raise walls, walls in the heart, walls on the land, in order to prevent this encounter with other cultures, with other people. And those who raise walls will end up as slaves within the very walls they have built. They are left without horizons, for they lack this interchange with others” (FT 27).

He touches upon the problems of injustice, arms race, induced poverty, racism, fears and apprehensions connected with migration, etc., as problems to be tackled in a Franciscan way (FT 28-55). After a detailed analysis of the present situation of the world in the first chapter, the Pope dwells upon the parable of the Good Samaritan in the second chapter. The parable of the Good Samaritan is very dear to St. Francis. His own life with the lepers outside the city walls of Assisi had a lasting impact on the life and mission of St Francis.

To feel indignant at the instance of human suffering, to be challenged to come out of our comfortable isolation and to be changed by our service to the suffering person is the sign of human dignity, says the Pope (FT 68). Commenting on the Priest and Levite in the story, the Pope writes: “It shows that belief in God and the worship of God are not enough to ensure that we are actually living in a way pleasing to God. A believer may be untrue to everything that his faith demands of him, and yet think he is close to God and better than others” (FT 74).

It is hypocrisy and arrogance of its members that has harmed the Church more than its dogmatic errors and liturgical freedom. We cannot but be shocked at the incident of Francis giving the Bible to someone who came to him asking for food, to be sold so as to procure food; he had done the same with the costly altar linen too, when he found that nothing else valuable was available!

In the third and fourth chapters the Pope speaks on the need to envisage and engender an open world and to open our hearts to the whole world. Pope Francis points out that ‘Solidarity’ has become a dirty word among certain sections of people (white collar Christians!) and he pleads to recover it with its full meaning. “Solidarity means much more than engaging in sporadic acts of generosity. It means thinking and acting in terms of community… Solidarity, understood in its most profound meaning, is a way of making history, and this is what popular movements are doing” (FT 116).

In the fifth chapter that deals with ‘a better kind of Politics’, Pope Francis brings in a typical Franciscan value ‘tenderness’ that is not to be mistaken for weakness. “Politics too must make room for a tender love of others. ‘What is tenderness? It is love that draws near and becomes real. A movement that starts from our heart and reaches the eyes, the ears and the hands… Tenderness is the path of choice for the strongest, most courageous men and women’. Amid the daily concerns of political life, ‘the smallest, the weakest, the poorest should touch our hearts: indeed, they have a ‘right’ to appeal to our heart and soul. They are our brothers and sisters, and as such we must love and care for them’” (FT 194).

The tender love of the mother towards the weakest child was the example given by Francis to take care of the sick brothers, and of course it applies to the poorest of the poor too. Here we are reminded of the Gandhian principle: “Sarvodaya through anthyodaya” – the progress of everyone can be guaranteed only by a special preference and option for the uplift of the last and the least in any society.

The fifth and sixth chapters are dealing with dialogue, encounter and friendship contributing towards global fraternity and harmony. He opens this section with a comprehensive, but simple explanation of the term ‘dialogue’. “Approaching, speaking, listening, looking at, coming to know and understand one another, and to find common ground: all these things are summed up in the one word ‘dialogue’” (FT 198). The Damietta Peace Initiative, inspired by St. Francis and organised internationally by the Capuchin Franciscans, has been actively engaged in dialogues for peace, especially in Africa. One can hardly forget the touching story of Francis successfully negotiating with the ferocious Wolf of Gubbio, as well as his interventions for peace between Assisi and Perugia.

In his typical Franciscan style the Pope introduces the term ‘Kindness’ into the context of dialogue and encounter. “Kindness frees us from the cruelty that at times infects human relationships, from the anxiety that prevents us from thinking of others, from the frantic flurry of activity that forgets that others also have a right to be happy. “Often nowadays we find neither the time nor the energy to stop and be kind to others, to say ‘excuse me’, ‘pardon me’, ‘thank you’. Yet every now and then, miraculously, a kind person appears and is willing to set everything else aside in order to show interest, to give the gift of a smile, to speak a word of encouragement, to listen amid general indifference... Kindness ought to be cultivated; it is no superficial bourgeois virtue. Precisely because it entails esteem and respect for others, once kindness becomes a culture within society it transforms lifestyles, relationships and the ways ideas are discussed and compared. Kindness facilitates the quest for consensus; it opens new paths where hostility and conflict would burn all bridges” (FT 224).

It is significant that Pope Francis makes it clear that every possible social conflict and protest cannot be condemned in the name of peace and forgiveness, because it may go against human dignity and justice (FT 240-244). This is something that is often neglected and even negated in our preaching! In the same way the Pope calls war and death penalty wrong answers and false solutions even in extreme situations. He affirms an emphatic “No” to the arguments for “just war” and “death penalty” (FT 255-263).

The concluding chapter of the encyclical dealing with “Religions at the service of Fraternity” begins with a paragraph quoting the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India: “The goal of dialogue is to establish friendship, peace and harmony, and to share spiritual and moral values and experiences in a spirit of truth and love” (FT 271). The long experiences of inter-religious dialogue under the auspices of the Bishops’ Conferences of India and Asia have proved that we have to go beyond dialogues on ‘scriptures and cultures’ and come to the ‘dialogue of life’, promoting life in all its aspects and definitely, for all people.

Pope Francis underscores once again what he has been emphasising from the beginning of his pontificate, viz., the nature and function of the Church. It is also a crisp and clear answer to those who hang on to a statement in the Vatican II Document on Liturgy that ‘liturgy is source and summit of the Church’.

The Pope declares without any room for ambiguity: “The Church is a home with open doors, because she is a mother. And in imitation of Mary, the Mother of Jesus, we want to be a Church that serves, that leaves home and goes forth from its places of worship, goes forth from its sacristies, in order to accompany life, to sustain hope, to be the sign of unity… to build bridges, to break down walls, to sow seeds of reconciliation” (FT 276).

Towards the end of the encyclical, Pope Francis becomes aesthetic and poetic about the music of the true Gospel, touching the hearts of the readers radiating joy and hope in the future. He emphasises the position of the Second Vatican Council that the Church esteems all religions, rejects nothing of what is true and holy in these religions and has a high regard for their manner of life and conduct, their precepts and doctrines which… often reflect a ray of that truth which enlightens all men and women (Nostra Aetate 2). Then he continues: “Yet we Christians are very much aware that ‘if the music of the Gospel ceases to resonate in our very being, we will lose the joy born of compassion, the tender love born of trust, the capacity for reconciliation that has its source in our knowledge that we have been forgiven and sent forth. If the music of the Gospel ceases to sound in our homes, our public squares, our workplaces, our political and financial life, then we will no longer hear the strains that challenge us to defend the dignity of every man and woman’” (FT 277). Considering our history as a common journey to a shared destiny, the Pope writes: “A journey of peace is possible between religions. Its point of departure must be God’s way of seeing things. ‘God does not see with his eyes, God sees with his heart. And God’s love is the same for everyone, regardless of religion. Even if they are atheists, his love is the same’” (FT 281).

The common appeal made by the Pope and the Grand Imam Ahmad al-Tayyeb in 2019 is inserted into the encyclical as its conclusion, followed by two prayers, one addressed to the creator, which can be said by the members of all religions and the second, an ecumenical Christian prayer, which can be said by all the Christians (FT 285).

Let me conclude by making three observations one should not fail to see:

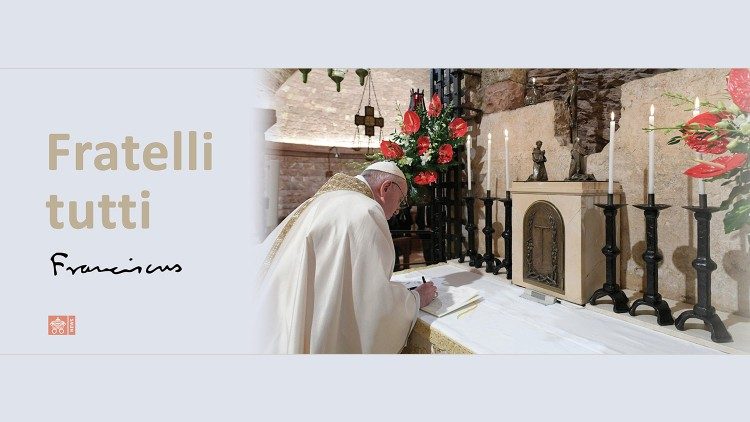

(1) The simplicity of the Pope in the simple ceremony of signing the encyclical at the tomb of St. Francis at Assisi on October 3 and praying for his intercession;

(2) The humility and openness to acknowledge that he was influenced by great saints and sages like Francis of Assisi, Charles de Foucauld in Africa, American civil rights campaigner Martin Luther King Jr., Anglican Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu of South Africa and Mahatma Gandhi of India; and

(3) The fraternal collaborative spirit and openness to the Holy Spirit that is evident in his acknowledgement that numerous people have contributed to the composition of the encyclical directly or indirectly.