.png) Joseph Maliakan

Joseph Maliakan

.jpg)

With the massive majority of the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) in the Parliament and the Union government’s increasing tendency to unilaterally bring in sweeping legislation and issue executive orders with adverse consequences for the states’ finances, the question of state autonomy has assumed special importance. With the victory of DMK in Tamil Nadu and the Trinamool Congress in West Bengal and the increasing clout of the Shiv Sena, NCP and the Congress combine in Maharashtra, the demand for state autonomy will only increase in the coming days.

In 1969 Chief Minister Annadurai, the founder of the Dravida Munnettra Kazhagam (Dravida Progressive Federation) and the then Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, wrote, “If by being in office the DMK is able to bring to the notice of the thinking public that the present Constitution is a sort of diarchy by the backdoor, that would be a definite contribution to the political world.”

The DMK, formed in 1949 as a breakaway faction of the Dravidar Kazhagam, headed by Periyar E.V. Ramaswamy had initially demanded a separate Dravida Nadu comprising areas of the Madras Presidency of the British India. The party formally gave up the demand in 1963 after the Sixteenth amendment to the Constitution criminalized separatism.

The 1967 election manifesto of the DMK stated: “The DMK has taken upon itself the responsibility of seeing that no region of the country dominates another region in the name of integrity. The DMK is determined to protect the rights of the states from being suppressed and to chalk out a plan for the uniform economic development of all the states and to transfer the residuary powers to the states. It will reiterate its demand to amend the Constitution for this purpose.”

Moving a resolution on autonomy in the State Assembly on 16 April 1974, M. Karunanidhi, then Chief Minister, said, “I am confident that this epoch-making resolution will be a landmark in the history of India.”

Diarchy was the system of double government introduced by the British in India through the Government of India Act 1919 for the provinces of British India. It was introduced as a constitutional reform by Edwin Montague, Secretary of State for India (1917-22), and Lord Chelmesford, Viceroy of India (1916-21). The system was based on the principle of division of the executive branch of each provincial government into authoritarian and popularly responsible sections.

The first was composed of Executive Councilors appointed by the Crown. The second was composed of Ministers who were chosen by the Governor from the elected members of the provincial legislatures. The latter Ministers were Indians.

The subjects of administration were divided between the Councilors and the Ministers, named reserved and transferred subjects, respectively. The reserved subjects under the heading Law and Order comprised justice, police, land revenue and irrigation. Transferred subjects included local self government, education, public health, public works, agriculture, forest and fisheries. The system ended with the introduction of provincial autonomy in according to the Government of India Act, 1935.

Independent India’s Constitution, in making the distribution of legislative powers between the Union and the States, adopted the method followed in the Government of India Act,1935. The various subjects of legislation have been enumerated in three lists: List I or the Union List; List II or the State List; List III or the Concurrent List.

The Parliament has exclusive power of legislation with respect to 97 subjects in List I. The State Legislatures have exclusive power with respect to 66 subjects enumerated in List II. The power in respect of 47 subjects in List III are concurrent, both the Union and State Legislatures can make laws in respect of these subjects. But in the event of a conflict between the two on a matter in the Concurrent List, the Union Act will override the State Act.

The Union-State relations in independent India reached breaking point in 1965 with the anti-Hindi agitation led by the DMK which brought life to a standstill in the southern States particularly Tamil Nadu. The agitation gave rise to the slogan “Autonomy to the States, Federalism at the Centre.”

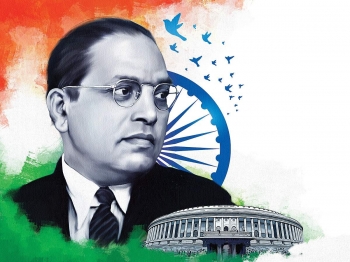

However, Article 356, enabling the Union Government to impose President’s rule in the States, has been the most controversial provisions of the Constitution. Under the provision, State Governments have been dismissed by the Union Government on 125 occasions in the last 75 years. Alas, in the Constituent Assembly, B. R. Ambedkar had hoped that the provision will remain a dead letter to be used as a last resort.

The unbridled resort to Article 356 came to a halt after the landmark Supreme Court judgment in the S.R. Bommai vs Union of India (1994) 2SC 215. In the Bommai case, the Supreme Court held that the State Government losing the confidence of the House should be decided on the floor of the House, that the dissolution of a State Assembly by presidential proclamation is subject to judicial review and if the court finds any mala fide it will strike down the proclamation and restore the Ministry of the State.

Mercifully, the Modi-led Union government has not used the provision of Article 356 not even once. But it has struck at the very basis of federal principles of governance by legislating on subjects exclusively reserved for the States and appointing Governors who have been working at cross purposes with elected State governments. The conduct of the Governors of West Bengal, Maharashtra and Kerala has been particularly shameful in many respects.

The three controversial farm laws, the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), and the attempt to bring education and health under the control of the Union Government are steps towards making the State governments mere supplicants.

There have been several attempts in the past to redefine relations between the Union and the States.In1969 the Tamil Nadu government set up one-member Justice P.V. Rajammanar Committee to suggest amendments to the Constitution to make the States autonomous. In its report submitted in1971, the committee suggested the Union Government should make laws affecting the States only with the concurrence and consent of the Inter State Council. It also suggested the abolition of all India services like the IAS, IPS and IFS.

The Sarkaria Commission appointed in 1983 made a number of recommendations to decentralize power. About the appointment of Governors of States the Commission recommended that the Prime Minister should consult the Vice-President of India and the Speaker of the Lok Sabha.

In 2000 the Union Government appointed the National Commission to review the working of the Constitution under the Chairmanship of Justice M. N. Venkatachaliah. The Commission recommended the constitution of a statutory body called Inter State Trade and Commerce Commission for consultations on matters between the States and the Union. It also suggested that the Governors of States should only be appointed by a Committee consisting of, among others, the Chief Minister of the State concerned.

The UPA government in 2007 appointed the M. N. Punchhi Commission to study the role and responsibilities of various branches of Union and State governments. The commission recommended that Governors should be appointed from a panel prepared by the legislature of the State concerned. Governors should not be made Chancellors of the Universities, the Commission stressed.

So far successive Union Governments have chosen to ignore the recommendations of various commissions because it involved giving away some of the enormous powers it enjoys. And going by the latest decision to lease out government properties across India, announced by the Union Government, it is in no mood to give even an inch of breathing space to the States. India is fast moving towards the 1919 British Era Dyarchy.