A. J. Philip

A. J. Philip

Crucifixion is what made Jesus great. In the case of Gautam Buddha, it was his abdication of the throne, and in the case of MK Gandhi, it was his decision to give up his upper garments to identify with the masses, beautifully captured in Richard Attenborough's Oscar-winning biopic and his eventual martyrdom.

Nelson Mandela showed greatness when he appointed a Truth Commission rather than wreaking vengeance on the white rulers who jailed him for 27 years. In recent times, Alexei Navalny became my hero—not for standing up to Vladimir Putin, but for returning to Russia after surviving a botched assassination attempt and undergoing a successful seven-month treatment in Germany.

Many, like this writer, considered him a fool to return when he could have remained in the Western world and coordinated the Opposition against the dictator, like the Iranian cleric who guided the movement against the Shah from the comforts of Paris. For a moment, I thought his decision to return was part of a deal with the Putin administration.

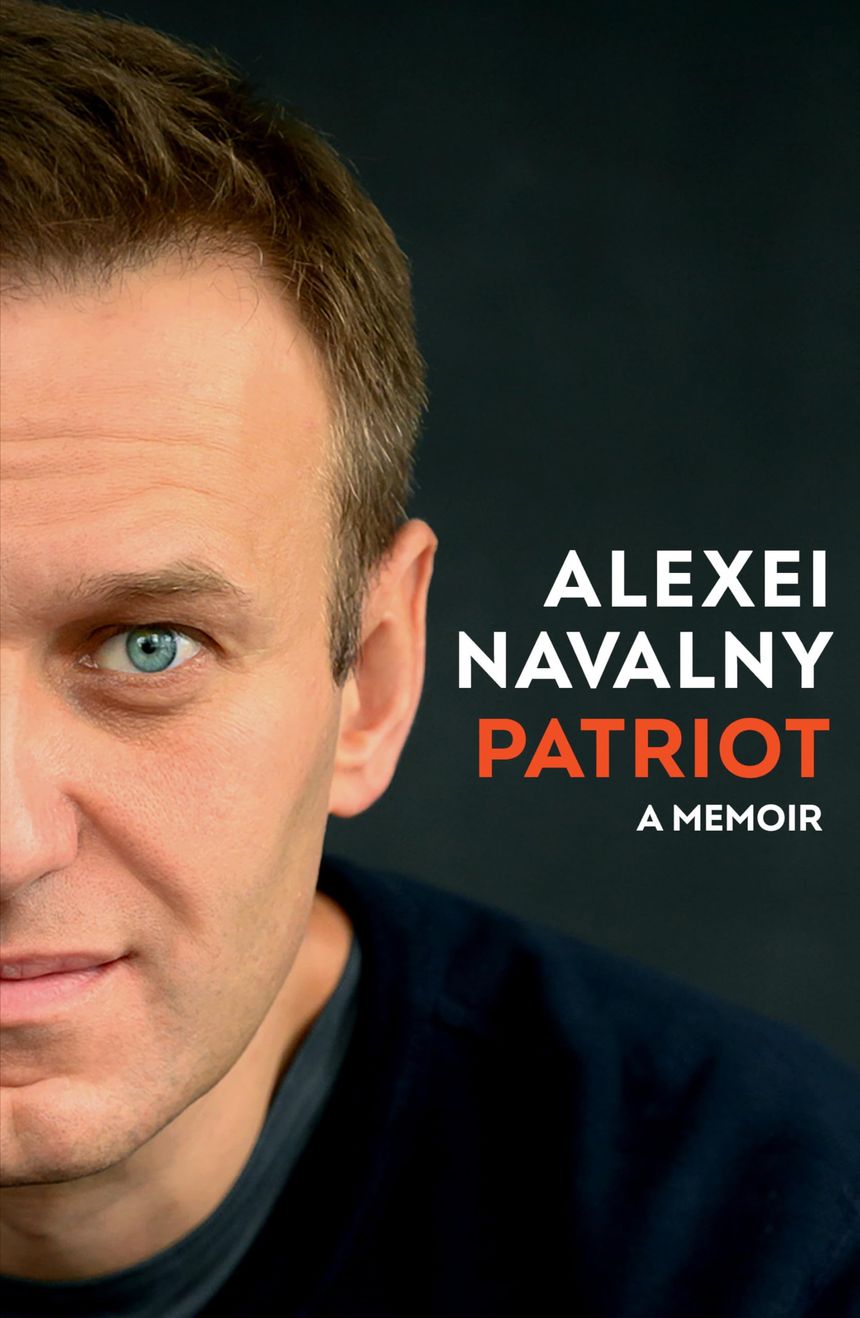

In his autobiography, Patriot (Penguin, 479 pages, ?1,399), published simultaneously in 22 languages last month, Navalny expresses his exasperation over the query about the deal. "I took part in elections and vied for leadership positions. The call for me is different. I traveled the length and breadth of the country, declaring everywhere from the stage, 'I promise that I won't let you down, I won't deceive you, and I won't abandon you.' By coming back to Russia, I fulfilled my promise to the voters. There need to be some people in Russia who don't lie to them."

His life story is at once moving because he writes without embellishments, straight from the heart. It has two parts: his life in a military area, as his father was in the army, and his personal experience when a nuclear reactor in Chernobyl began leaking radioactive substances. He learned, to his chagrin, how the government tried to cover up the nuclear disaster, fully aware it would adversely affect the health of tens of thousands of people.

People in the West knew more about the dangers of the disaster than those living in close proximity to Chernobyl, like the Navalnys. For once, he learned that deception and lies were the foundations on which the Soviet system was built. His descriptions of the period when his mother had to stand in long queues to buy meat and how he cursed himself while standing in line every day for milk sharply contrast with the descriptions of life in Soviet publications like Soviet Land.

He concluded that a country not self-sufficient in milk had no claim to being a superpower. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), as it was known, lagged behind the West, especially the US, in every respect. However, the people had no knowledge of life outside the Iron Curtain as they had no travel opportunities, and strict censorship did not allow knowledge to seep through.

Navalny grew up aspiring to be rich, with an imported car—the status symbol of the neo-rich. He craved a Western education that would enable him to be a successful chief executive. In the end, he became a lawyer with enough income to rent premises in Moscow, no longer having to wait for hours to catch a rickety bus where entry was possible only for the well-muscled.

The economic and social reforms initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the USSR, did not impress him because Gorbachev lacked the courage to take them to their logical culmination. Gorbachev lacked both faith in market forces and the ability to overcome the challenges posed by the establishment that ran the Soviet empire for nearly seven decades. Like King Lear, Gorbachev could only watch in despair as his own decisions spun out of control.

Boris Yeltsin, who replaced him, was a dyed-in-the-wool apparatchik for whom democracy meant nothing but another way to consolidate power. He managed to exploit the feelings against Gorbachev, who sought to reduce alcohol consumption, for his own good and not the welfare of the people. Navalny's hopes that Yeltsin would usher in positive change were soon belied. All Yeltsin could do was dismember the Soviet Union and convert Russia into what the USSR was.

Navalny realised sooner than later that none of the political parties that sought to fill the vacuum created by the displacement of Communist hegemony was truly democratic by instinct or practice. He went to a party with the desire to join, only to be told to wait a whole year because admission was not given to anybody for the asking. The party leaders could not even believe that a person with a reasonably good job would contemplate joining a political party to serve the nation.

It was in this flux that Vladimir Putin emerged as the leader. He was the head of the Soviet intelligence agency, the KGB, notorious for its dirty tricks both within and outside the country. The whole edifice of the KGB was built on lies, and if anyone thought Russia would become a democratic state under him, they lacked even an iota of understanding of the Putin psyche. He was an out-and-out dictator who believed destiny wanted him to be the Tsar or Party Secretary of yesteryears.

When Navalny found that he could not jump on any political bandwagon to challenge Putin's supremacy, he adopted other means, like exposing the Putin regime for what it was—narcissistic and built on corruption, nepotism, and violence. He found, to his dismay, that many public sector companies doing business worth billions of roubles were actually run in the style of the Italian mafiosi. He bought shares in some such companies not to earn dividends but to question the management at shareholders' meetings.

Corruption is deep-rooted in Russia. He founded an organisation to expose the corrupt. Russia was new to the Internet. Unlike China, which learned how to control the Internet before it became popular in the country, Russia did not know what it was. Meanwhile, Navalny's use of the Net went to such an extent that he made bold to film a video of the private palace Putin owns, which boasts state-of-the-art facilities, using aerial photography.

He exposed several top officials. Small wonder that he became a thorn in Putin's flesh. Then, the deep state began to attack him. Putin also realised that Navalny was no pushover, particularly after he contested the post of Mayor of Moscow. Though defeated, he won a sizeable percentage of votes. He was young, intelligent, and politically astute, with stamina to match.

Navalny believed that by coming to power, Putin deprived Russia of a chance for recovery. The country has enormous natural resources, like oil, and a small, educated population. The dismantling of Communism could have paved the way for market forces to intervene. Entrepreneurship could have been encouraged. Instead, Putin allowed crooks enjoying political patronage to become billionaires without any of them producing anything new, like an iPhone or a service like Amazon's.

In a short period, Navalny became the most popular political leader in Russia, with his face recognisable across the country. He also had political ambitions, as shown by his decision to file a nomination for the presidency. Putin feared he could indeed be defeated.

The dictatorial regime could think of only one way to face the challenge: eliminating Navalny physically. Thus, a plan was hatched and executed. Fortunately for Navalny, the regime, for some strange reason, allowed him to go to Germany for treatment, which saved his life. As mentioned earlier, he could have stayed in the West and continued his propagandist work against Putin.

But no, he wanted to return to his country, come what might. Many journalists were on the same flight, and nobody believed he would be allowed to clear the emigration check. And that's exactly what happened. Thereafter, Navalny devotes pages upon pages to his life in jail. Jail literature is already a genre, and his contributions are remarkable.

Though he is not privy to events in the outside world—like when a documentary on him won the Oscar—he gleans much from his meetings with his wife, who stands like a solid rock for him, and his lawyers. Even in jail, he is denied peace. New cases are repeatedly filed against him, and his sentences are extended longer and longer. The punishments grow harsher, with solitary confinement being a common tactic.

The worst treatment he endured was when a lunatic, who screamed and shouted day and night except when he slept, was placed in the cell adjacent to him to deprive him of sleep. Sleep deprivation is among the harshest weapons wielded by prison authorities. When he went on a hunger strike, Putin's foot soldiers taunted him by eating fried chicken in front of him. Finally, he was branded a terrorist and sent to Siberia, where he died from torture.

Despite all this, his sense of humour never left him. He felt "Christmassy" when Christmas came around despite the suffering inflicted on him. Navalny was not one to brandish religion. Born an atheist, like most Russians, he later realised that the birth of a child couldn't be described in biological terms alone. His faith became his constant companion—not just when he read the Bible, which was sometimes his only book. At other times, he had access to a plethora of works and read authors as varied as Charles Dickens and Yuval Noah Harari.

He read the Sermon on the Mount multiple times and even memorised translations of each verse in four languages—Russian, English, French, and Latin. However, he wasn't the type to pray three or four times a day, as many prisoners did. Instead, he held a deep conviction that, by modelling his life after Jesus, he had nothing to fear.

To quote Navalny, if you are "a disciple of the religion whose founder sacrificed himself for others, paying the price for their sins," and you trust "in the immortality of the soul and the rest of that cool stuff," then "what is there left for you to worry about?" He remained a devoted Christian until the end, trusting that "Good old Jesus and the rest of his family… won't let me down and will sort out all my headaches. As they say in prison here: they will take my punches for me."

While reading the book, I was reminded of the plight of prisoners like Fr. Stan Swamy and GN Saibaba, whose experiences bore striking similarities to Navalny's. Like him, they, too, have passed away. Many others—Umar Khalid, Surendra Gadling, Rona Wilson, Jyoti Jagtap, Hany Babu, Sagar Gorkha, Mahesh Raut, Ramesh Gaichol, Aasif Sultan, and Khurram Parvez—remain behind bars, prisoners of conscience in their own lands.

As for Putin and his oppressive regime, history teaches us that no tyranny lasts forever. His empire, built on lies and cruelty, will one day crumble like a house of cards. Yet, the legacy of a patriot like Alexei Navalny will endure, inspiring generations to come. As the saying goes, "The tyrant dies and his rule is over; the martyr dies and his rule begins."