.jpg) Prakash Louis

Prakash Louis

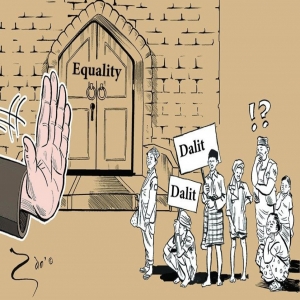

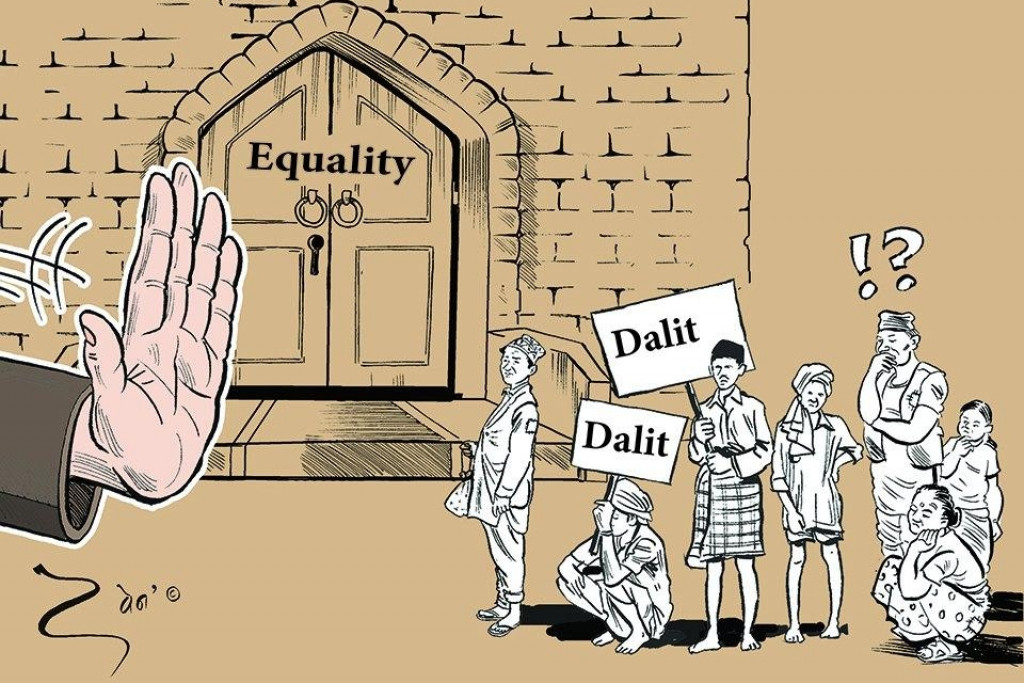

The constitutional guarantee of equality and fraternity has existed for more than seven decades in India. Constitutional safeguards cover over 201 million Scheduled Castes (16.6%) and 100 million Scheduled Tribes (8.6%). Thus, as per 2011 Census data, they constitute 25 per cent of the country's 1,330 million population. Realising the age-old exclusion the Scheduled Castes were subjected to and the exploitation the Scheduled Tribes had to undergo, the framers of the Constitution ensured that positive action, like reservation in jobs and places, were used to improve the condition of these weaker sections and guaranteed their legitimate rights.

But affirmative action has not been without its controversies, legislative quagmire and litigations. More than political reservation, job reservations and preferential treatment in educational institutions have been the bone of contention. The Indian social order, as well as the social mindset and the mainline media, divides Indians into two camps, pro and anti-reservationists. In this argument and counterargument, the issues around the reservation's importance, significance and status to the weaker sections are lost.

"Despite these seemingly attractive employment opportunities the dismal backwardness in the matter of representation in administration from among the SC/STs was such that the vacancies reserved for them remained, in many cases, unfilled by SC & ST candidates." This historic judgment was delivered by Justice VR Krishna lyer in the Akhil Bharatiya Soshit Karamachari Sangh (Railways) Vs Union of India on November 14, 1980, the day of his retirement. The significance of this judgment was that the late Justice Krishna Iyer delivered this verdict after a careful examination of the Indian social order. He also dissected the arguments of those who argue on the infallibility of 'merit' over 'inclusion' and exposed the arguments and those who propound the argument that reservation drastically brings down the work culture and ability in the public sector.

The recent verdict by the Supreme Court of India in the case, 'The State of Punjab & Ors. …Appellants Versus Davinder Singh & Ors. …' delivered by a seven-bench judge headed by the Chief Justice of India on August 1, 2024, made the following statements: "The reference to this Constitution Bench raises significant questions relating to the right to equal opportunity guaranteed by the Constitution. The principal issue is whether sub-classification of the Scheduled Castes for reservation is constitutionally permissible… Historical and empirical evidence demonstrates that the Scheduled Castes are a socially heterogeneous class. Thus, the state in exercise of the power under Articles 15(4) and 16(4) can further classify the Scheduled Castes if (a) there is a rational principle for differentiation; and (b) the rational principle has a nexus with the purpose of sub-classification; and (f) The holding in Chinnaiah (supra) that sub-classification of the Scheduled Castes is impermissible is overruled."

This landmark judgment by the Supreme Court of India, which permits sub-classification of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes to grant separate quotas for the more backwards within these weaker sections, has once again generated more heat and dust. The idea of positive affirmation was given a significant thrust in independent India through Articles 15(4), 15(5), 16(4), 16(4A), 16(4B), 330 and 332 of the Constitution of India. This provision is under threat now.

Caste in Principle and Practice

Justice Krishna Iyer, examining the two aspects of this debate - equality before the law and inequality in life, pointed to the root thought. "This agonising gap between hortative hopes and human dupes vis-à-vis that serf-like sector of Indian society, strangely described as scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, and the administrative exercises to bridge this big hiatus by processes like reservations and other concessions in the field of public employment is the broad issue that demands constitutional examination in the Indian setting of competitive equality before the law and tearful inequality in life. A fasciculus of directions of the Railway Board has been attacked as an ultravirus, and the court has to pronounce it, not philosophically but pragmatically."

A careful reading of this historical verdict delivered by Justice Krishna Iyer points out the ridiculous level the Indian caste mindset can descend to claim that railway accidents are due to reservations.

"Caste, undoubtedly, is a deep-seated pathology to eradicate, and the Constitution took care to forbid discrimination based on caste, especially in the field of education and services under the state. The rulings of this court, interpreting the relevant Articles, have hammered home the point that it is not constitutional to base the identification of backward classes on caste alone. If a large number of castes masquerade as backward classes and perpetuate that division in educational campuses and public offices, the whole process of a caste-free society will be reversed. We are not directly concerned with backward classes as such, but with the provision ameliorative of the SC/STs. Nevertheless, we have to consider seriously the social consequences of our interpretation of Art. 16 in the light of the submission of counsel that a vested interest in the caste system is being created and perpetuated by over-indulgent concessions, even at promotional levels, to the SCs/STs. which are only a species of castes. 'Each according to his ability' is being substituted by 'each according to his caste,' argue the writ petitioners and underscore the unrighteous march of the officials belonging to the SCs/STs over the humiliated heads of their senior and more meritorious brothers in service. The aftermath of the caste-based operation of promotional preferences is stated to be a deterioration in the overall efficiency and frustration in the ranks of members not fortunate enough to be born SCs/STs. Indeed, the inefficiency bogie was so luridly presented that even the railway accidents and other operational calamities and managerial failures were attributed to the only villain of the piece, viz., the policy of reservation in promotions. A constitutionally progressive policy of advantage in educational and official careers based upon economic rather than social backwardness was commended before us by counsel as more in keeping with the anti-caste, pro-egalitarian tryst with our constitutional destiny."

Reservation: Myth and the Reality

An examination of the socio-economic profile of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes shows no marked improvement in their socio-economic and educational condition even after seven decades of implementation of planned development. No significant progress has been seen due to the provisions of reservation policies. Even in the examination of an ordinary indicator like literacy rate, these communities lag behind. Moreover, universal enrollment was supposed to pay special attention to children from Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Attractive slogans, like 'Universalisation of Primary Education', 'Compulsory and Free Education', and 'Making Education an Enjoyable Exercise', continue to be used by the political establishment regularly. But in reality, they have not introduced a substantial change in the state of these weaker sections.

The percentage of reservation in direct recruitment on an all-India basis by open competition for SCs and STs was fixed as 15% and 7.5%, respectively, vide MHA Resolution No. 27/25/68-Estt. (SCT) dated March 25, 1970. However, contrary to common belief and the projections made by mainline media, the percentage of members from weaker sections employed in government services based on reservation in public service is abysmally low. If one pays attention to their presence in the government services, one would be shocked that even the stipulated 15 and 7.5%, respectively, of the reservation quota fixed for these communities, is not filled. Many of these prescribed posts are filled up by the dominant castes. As per the Annual Report 2020-21, Department of Personnel and Training: Government of India, New Delhi, 2021-2022, only 13.01% of the 15.0% determined for reservation for the Scheduled Castes, and only 5.89% of the 7.5% allotted to the Scheduled Tribes has been filled as late as 2022.

Table 1: Representation of SCs/STs in Central Government Services

|

Group |

Total Number of Employees |

Scheduled Caste |

Scheduled Tribe |

||

|

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

||

|

A |

77,429 |

10,072 |

13.01 |

4,558 |

5.89 |

|

B |

1,47,860 |

24,802 |

16.77 |

10,480 |

7.09 |

|

C (Excluding Safai Karmcharis) |

16,08,901 |

2,79,284 |

17.36 |

1,26,084 |

7.84 |

|

C (Safai Karmcharis) |

44,632 |

14,534 |

32.56 |

3,148 |

7.05 |

|

Total |

18,78,822 |

3,28,692 |

17.49 |

1,44,270 |

7.68 |

Source: Annual Report 2020-21. Department of Personnel and Training: Government of India. New Delhi. 2021- 2022, p 33.

It is significant to note that when it comes to 'demeaning employment' like being recruited as Safai Karmcharis, there is no competition with these weaker sections. Here there is a 100 per cent reservation only for them. Persons from other castes will become 'Director, Administrator and Finance Officer' of this sector but not engage in scavenging. This is the deep-seated decadency that the anti-caste movements have been waging war against. Hence, any discussion on reservation should pay attention to these inherent and inbuilt caste practices in the Indian social, economic, political, cultural, religious and mental makeup.

Moreover, in every sector, discrimination is practised without any penalty. The Committee on the Welfare of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, in its report presented to the Parliament on March 15, 2000, pointed out that out of 481 judges in High Courts, there are only 15 judges from the Scheduled Castes. This is just over 3.11%. If the population of the Scheduled Castes is 16.48% and over five decades of affirmative action did not ensure their due presence in the judiciary, the interests of this community cannot be served. The report further states: "The members of the judiciary have so far been drawn from the very section of society which is infected by ancient prejudices and is dominated by notions of gradation in life. The internal limitation of class interests of such judges does not allow them full play of their intellectual honesty and integrity in their decisions. Their judgments very often betray a mindset more useful to the governing class than to the governing class than to the servile classes and no sympathy for any real measures designed to raise their dignity and progress."

It is amusing how the Department of Personnel and Training of the Government of India describes the status of reservation of the SCs and STs through direct recruitment. Representation of SCs/STs has increased in all the Groups viz. A, B, C and D during the last six decades. At the dawn of independence, there was very little representation of SCs/STs in services. As per available information, the representation of SCs in Groups A, B, C and D as of January 1, 1965, was 1.64%, 2.82%, 8.88% and 17.75%, respectively, which has increased to 12.5%, 14.9%, 15.7% and 19.6% respectively as on January 1, 2008. Likewise, while the representation of STs as of January 1, 1965, in Group A, B, C and D was 0.27%, 0.34%, 1.14% & 3.39%, respectively, it only increased to 4.9%, 5.7%, 7.0% and 6.9% respectively as on January 1, 2008. The total representation of SCs and STs as of January 1, 1965, was 13.17% and 2.25%, respectively, which increased to 17.51% and 6.82%, respectively, on January 1, 2008.

Table 2: Representation of SCs and STs over Decades in Services

|

As on 1st of January |

Group A |

Group B |

Group C |

Group D |

Total |

|||||

|

SCs |

STs |

SCs |

STs |

SCs |

STs |

SCs |

STs |

SCs |

STs |

|

|

1965 |

1.64 |

0.27 |

2.82 |

0.34 |

8.88 |

1,14 |

17.75 |

3.39 |

13.17 |

2.25 |

|

1970 |

2.36 |

0.40 |

3.84 |

0.37 |

9.27 |

1.47 |

18.09 |

3.59 |

13.09 |

2.40 |

|

1980 |

4.95 |

1.06 |

8.54 |

1.29 |

13.44 |

3.16 |

19.46 |

5.38 |

15.67 |

3.99 |

|

1990 |

8.64 |

2.58 |

11.29 |

2.39 |

15.19 |

4.83 |

21.48 |

6.73 |

16.97 |

5.33 |

|

2001 |

11.42 |

3.58 |

12.82 |

3.7 |

16.25 |

6.46 |

17.89 |

6.81 |

16.41 |

6.36 |

|

2008 |

12.50 |

4.90 |

14.90 |

5.70 |

15.70 |

7.00 |

19.60 |

6.90 |

17.51 |

6.82 |

Source: Objective of Reservation. Department of Personnel and Training of the Government of India. An undated document, p 7.

Even a cursory glance at the data provided in Table 2 highlights that even after 5 decades of implementation of reservation, the seats allotted in jobs in group A have not been filled. Governments after governments have failed miserably to ensure this. Petitions after petitions filed in the honourable courts have not resulted in the implementation of constitutional provisions. Secondly, the shift in the percentage of services in both these communities is clearly seen from the 1980s. This is because, by this time, Dalit and Tribal activists, intellectuals, NGOs, civil society organisations and political parties representing these communities began to raise questions about the non-fulfilment of the seats.

Creamy Layer Debate

In any discussion on the creamy layer, the following broad submissions are presented as a starting point based on legal measures. First, the creamy layer must be excluded from reservations at the entry-level and in promotions. Second, currently, the exclusion applies only to OBCs and not SC/STs. Third, the creamy layer exclusion should be applicable even for SC/ST reservations in light of the M Nagaraj case, which treats the differentiation in the Indra Sawhney case as obiter.

Some argue that the Supreme Court has tried to defend the idea of excluding the creamy layer through the doctrine of classification or sub-classification. According to this stand of the Supreme Court, a classification is reasonable if it satisfies two conditions. First, there must be an intelligible differentia in the class sought to be differentiated. Second, such a differentia must have a rational nexus with the object sought to be achieved by the statute or executive order. Recently, it was agreed that the object must be reasonable. It is argued now that if there is the possibility of intelligible differences that separate a group within a group, then there should not be any objection to further classification of that more extensive group.

Chronology of application of 'Creamy layer':

1975: Punjab issued a notification giving Balmiki & Mazhabi Sikhs preference in SC reservations.

2004: E V Chinnaiah v State of Andhra Pradesh—The Supreme Court said that states cannot subclassify SCs/STs.

2006, July: Dr Kishan Pal v State of Punjab – Punjab HC struck down Punjab's 1975 notification as per the Chinnaiah ruling. In October 2006, Punjab Govt. passed Punjab's SC and Backward Classes (Reservation in Services) Act 2006, reintroducing preference for Balmiki & Mazhabi Sikhs.

2010, July: The Punjab High Court struck down the 2006 Punjab Act, which was later challenged in the Supreme Court.

2014: Davinder Singh v State of Punjab – Referred to a 5-judge Constitution Bench.

2020: The Constitution Bench questioned the Chinnaiah case and referred the case to a larger bench.

2024: A 7-judge Bench (6:1) overturned Chinnaiah's case judgment, allowing states to sub-classify SC/ST and set sub-quotas for backward communities. Supreme Court upholds quota within quota for marginalised within the SCs and STs.

The recent Supreme Court Verdict has directed the following: "State must evolve a policy to identify creamy layer among the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes category and exclude them from the fold of affirmative action," Justice Gavai was quoted as saying by Live Law. Thus, the Supreme Court overruled a 2005 judgment that ruled that SC/ST sub-classification was contrary to Article 341 of the Constitution. The particular Article confers the right of the President of India to prepare the list of SCs and STs. While disposing of the case, the bench stated: "There is nothing in Article 15, 16 and 341 which prevents sub-classification for SCs if there is a rational for distinction (intelligible differentia) and there is a rational nexus for the object sought to be achieved. State can sub-classify for the inadequate representation of some class" The court, however, cautioned that states must support sub-classification with empirical data, ensuring it is not based on "whims or political expediency."

Creamy Layer Debate: Some Concerns

First of all, the creamy layer proposal is seen as a part of the natural apathy of the upper strata of the society towards the Dalits and the Tribals. These communities also understand from their experiences that whatever proposals are suggested concerning the reservations are all aimed at raising some dust against it. Hence, the Tribals and Dalits perceive the creamy layer proposal as yet another stroke to dilute the spirit of the reservations to further exclude them.

Secondly, the Supreme Court has done mighty little to challenge the non-implementation of positive discrimination. As observed in the previous pages, even after seven decades of implementation of reservation policy, the picture is abysmal. The judicial system should engage with the government to put in place penal provisions for those who fail to implement the reservation policy.

The creamy layer proposal at this juncture may also threaten the overall progress of developing a middle class among the SCs and STs. With all its limitations, reservation has enabled a small segment of these communities to get educated and employed to provide leadership to these communities in social, political, economic, and religious sectors. Due to the articulation and assertion from this section, the issues of the Tribals and Dalits are kept alive.

The Dalits and Tribals resent the fact that under the garb of the creamy layer, there is an attempt to divide and rule. It is a fact that the Dalits and Tribals are not homogenous groups. They have divisions based on social, economic, political, educational and religious identities and backgrounds. Yet, when it comes to identity politics and when the entire community is challenged, then the Tribals and the Dalits function in unison. These communities now see the creamy layer debate as an attempt to undo this unity. Further, these communities want the debate of sub-classification to remain an internal issue and not imposed by vote bank politics or upper caste bias. Let the communities devise ways and means to address the differentiation among them.

"The UPA Government is very sensitive to the issue of affirmative action, including reservations in the private sector. It will immediately initiate a national dialogue with all political parties, industry and other organisations to see how best the private sector can fulfill the aspirations of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes youth". This statement of the Common Minimum Programme (CMP) of the United Progressive Alliance created more debate than any other programme.

The opposition came for this from many quarters. Sunil Kumar Munjal, the President of CII, argues the case by stating, "We cannot be forced to take individuals who don't have the required skills. We cannot afford to compromise on efficiency. That would affect our competitiveness. We cannot compromise on merit. The corporate sector does not go by colour of skin, caste or the last name." However, the reality is that corporations recruit only those from their social settings.

Even as early as 2004, when affirmative action in the private sector was going on, the following concrete measures were suggested: an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission be constituted to review and ensure that the weaker sections find their representation at all levels. Make special provisions for higher education, responsive training, and multi-skilling of the tribals and Dalits so that they can compete with others for jobs. Empower National Commissions for SCs and STs so that they work as a pressure group on the government and the private sector for the right to participatory development. Finally, ensure nationwide debate on these issues and introduce necessary constitutional amendments to enact affirmative action at all levels in the private sector. But all these remained only on paper.

Further, the Tribals and Dalits have been demanding land and redistribution, non-encroachment of land in the name of development, distribution of surplus land, comprehensive rehabilitation policy determined by the Tribals, implementation of Forest Right Act, life skill education, opening in higher education, employment, housing, access to proper public health, entrepreneurship development, implementation of Special Component Plan and Tribal Sub-Plan, and separate electorate for the Scheduled Castes. If the earlier regimes were based on Brahminism and capitalism, the present regime is driven by Hindutva and neo-liberalism. All these deny the Dalits and the Tribals citizenship based on liberty, fraternity and equality. Unless the demand of Dr Ambedkar to incorporate social democracy as fundamental to political and economic democracy is realised, the creamy layer will perpetuate and not annihilate the draconian caste system of India.