The relationship between sexual violence and caste in India exposes ingrained social injustices that have persisted for decades despite the country's independence. Even though equality before the law is guaranteed by the Indian Constitution, people from marginalised communities—especially Dalits—often experience a very different reality. In India, caste has a significant influence on sexual violence and is not just a problem for one gender. The victim's caste often dictates the reaction of the legal system, public indignation, and media coverage. This piece examines the widespread problem of rape in India, emphasising the particular difficulties faced by Dalit women and how caste affects justice.

India's caste system, though legally abolished, continues to govern social, economic, and political life. Caste determines one's status and opportunities. The caste system dictates an individual's standing and prospects, and Dalit women frequently experience dual oppression as members of a marginalised caste and as women. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) states that a crime against Dalits is committed every fifteen minutes and that six Dalit women are raped every day. In spite of these concerning figures, Dalit victims frequently do not garner the same level of attention or condemnation as women from higher castes, highlighting the systematic discrimination that exists in Indian society.

There was a lot of public outrage, quick political responses, and media coverage of the upper-caste victim in the Bengal case. In contrast, the Bihar incident, in which a Dalit girl was the victim, received little attention from the media and generated little political or public outcry. The dearth of response in the Bihar case was partly caused by the victim's caste, underscoring the institutionalised prejudice in the way these cases are managed.

There has long been a pattern of caste-based inequality in rape cases. A prime example of this inequality is the 2020 Hathras case, in which a young Dalit woman was brutally raped and killed. Government agents swiftly suppressed those pursuing justice, destroyed evidence, and dropped the case. The 2012 Nirbhaya case, on the other hand, involving a victim from the upper caste, caused a great deal of outrage, important legal changes, and even a special session of the Supreme Court. While the Nirbhaya case became emblematic of India's struggle against sexual violence, it also exposed the partiality of public and judicial support.

Although frequently biased, the media plays a critical role in influencing public opinion and the administration of justice. Storylines about victims from the upper caste are more likely to be sensationalised and to be reported non

The way the Indian judiciary and law enforcement operate is also influenced by caste dynamics. Crimes against Dalit women frequently result in intimidation of the victims' families, delays in the investigation, and refusals to file First Information Reports (FIRs). However, when it comes to victims who are from higher castes, the authorities tend to move quickly and decisively. These obstacles in the court system for Dalit victims are glaringly evident in the Hathras case, where authorities keep protecting the offenders ahead of serving justice.

Socio-economic factors make Dalit women especially susceptible to sexual violence. Dalit women frequently work in low-paying, unofficial jobs with little access to legal, medical, or educational resources. Since they lack the social and financial resources to defend themselves, their economic marginalisation makes them easy pickings for sexual assault. Due to the combination of economic disparity and caste, Dalit women are primarily dependent on upper-class employers or landlords who can take advantage of their weaknesses without worrying about the consequences.

Although there is a strong legal framework in place to prevent sexual violence, caste prejudice frequently makes it difficult for these laws to be implemented. Law enforcement usually uses the Prevention of Atrocities Act insufficiently or ignores it, which reflects ingrained prejudices and the intention of shielding Dalits and Adivasis from caste-based violence. Victims of dominant caste abuse frequently have few choices because of the perpetrators' frequent use of social and political influence to evade justice.

The social stigma attributed to Dalit women's gender and caste exacerbates the psychological effects of sexual violence against them. Knowing that they are more likely to be victims of violence and not get justice because of their caste exacerbates the trauma of rape. The widespread sense of helplessness and terror that accompanies this perception of Dalit women as second-class citizens contributes to long-term mental health problems, such as elevated rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts.

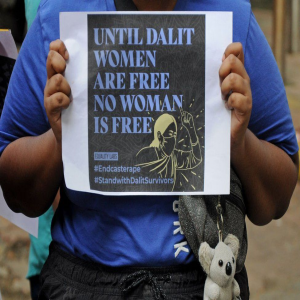

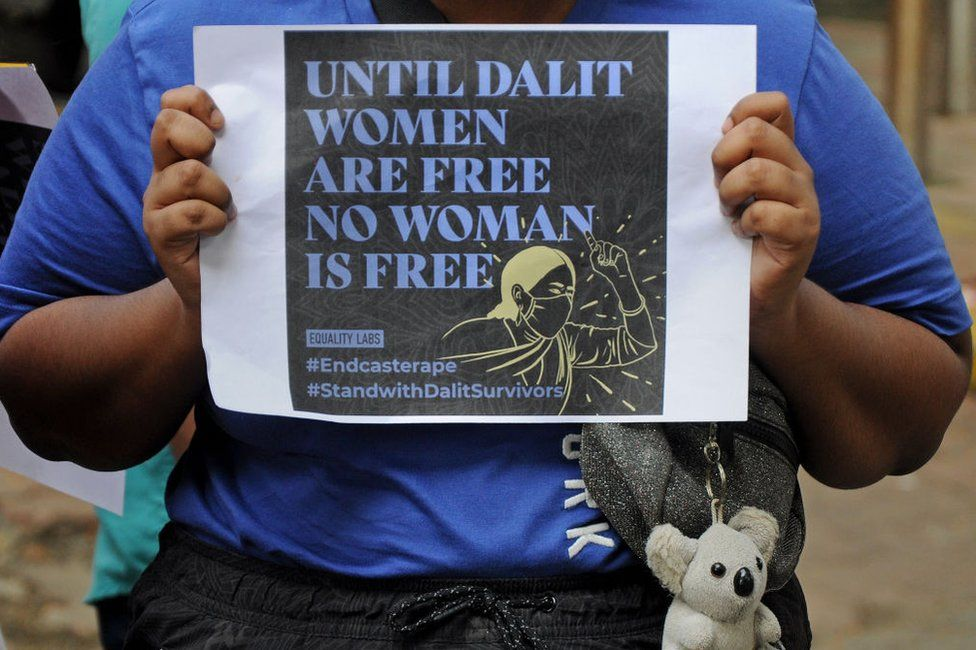

Dalit women and activists persist in resisting and fighting for justice in the face of these overwhelming obstacles. Dalit women's rights and legislative and policy changes have been spearheaded by groups such as the National Dalit Movement for Justice (NDMJ) and the All India Dalit Mahila Adhikar Manch (AIDMAM). These organisations empower Dalit women by battling systematic discrimination, spreading awareness, and offering legal support. The community's tenacity and resolve to end caste-based oppression are demonstrated by the increasing visibility of Dalit voices in the campaign against sexual assault.