A. J. Philip

A. J. Philip

The year: 2000! The Venue: The Vatican! A Capuchin priest and I are waiting for a Cardinal at the parlour. The aim: To meet him and seek an appointment with Pope John Paul II. If not, at least attend the Pope’s private mass in the morning. I was in Rome to report the Great Jubilee for the Indian Express, where I was the edit page in-charge.

I felt very uncomfortable sitting there as two Catholic nuns in their white habits were busy dusting the chairs. I could not check their national identity. They could have been from the Philippines. They were either octogenarians or septuagenarians. I felt terribly sad that they were working when they should have been enjoying the evening of their life. Forgive me for my presumptions.

The first time I ever saw Catholic nuns was when we primary class students were taken on an excursion at the Nooranad Leprosy Sanatorium. Today, it houses a battalion of the Central Reserve Police. At that time, the Sanatorium was large and lush-green with hundreds of leprosy patients.

I saw two white European nuns dressing the wounds of patients, some of whom had lost their nose and toes to the most dreaded disease. I was too young to understand why they came all the way from Europe to nurse the leprosy patients.

Years later, a film called Aswamedham was shot there. I remember the film because Valsala, who was once my sister’s classmate, played a leading role in the film as the main character, Sheela's younger sister.

What the nuns did remained a mystery to me till I read Mother Teresa, now Saint Teresa, explaining that when she and her sisters picked up a dying man from the gutters of Calcutta, they saw in him not a Bengali or an Oriya but the Jesus of Nazareth.

Now, let me take you to another venue: A five-star hotel in downtown Tokyo where a group of journalists from India, accompanying Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, were staying. We all had gone to a special Japanese restaurant where Japanese food was served in all its purity.

By the time we returned to the hotel, a new day had dawned. We saw two Japanese men, who could be in their eighties quietly working at the ground-floor restaurant. They were dusting and cleaning the floor and setting the tables right. I watched them from a distance. They were so engrossed in their work that they were not even talking to each other.

The two did not surprise me. The previous day, I had gone to the bookshop at the hotel where I met the lady in charge there. She was also an octogenarian who worked because she did not want to sit idle at home. Japan was a rich country as its economy was the world’s second largest.

From the conduct of the three Japanese I mentioned, I learnt how Japan, which was “finished” during the Second World War, rose like a phoenix bird in a few decades to become a wonder for the world.

For the Japanese, work is worship and they all prefer to die in harness. They are like the South Indian lady who told Nobel-laureate Amartya Sen that she washed clothes during her spare time. They were entitled to a good salary and they were doing a job. Was that the case with the elderly nuns I encountered at the Vatican?

Before I proceed further, let me mention the context in which I write this column. I was recently invited as a resource person at a three-day conference organised by the CRI (Conference of Religious India - Women) at Pune in Maharashtra. Attending the conference were administrators, principals and heads of various Catholic institutions in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Goa. They were mostly middle-aged sisters from all parts of the country.

After I delivered my speech and completed answering the questions from the assembled, one of the organisers of the conference presented to me a potted plant, which I left there as it would have been a hassle carrying it all the way back to Delhi, and a small book.

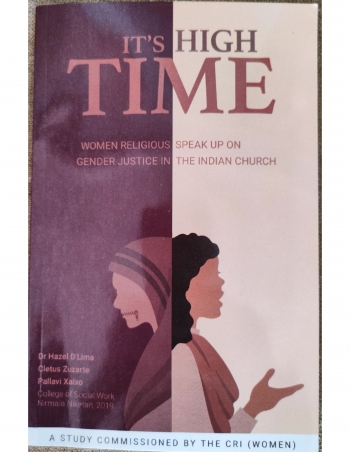

It was titled ‘It’s High Time: Women Religious speak up on gender justice in the Indian Church”, put together by Dr Hazel D’Lima, Clutus Zuzarte, Pallavi Xalxo and College of Social Work, Nirmal Niketan (Pages 86, Rs 100). I read the book in one go. Let me warn you, it is the report of a study conducted in 2019 and published in June 2021.

One book I noticed because of its title, bought it, read it and reviewed it is “If Nuns Ruled the World: Ten Sisters on a Mission” by Jo Piazza. The author provides a pen portrait of 10 remarkable nuns who changed the way we look at them. They were extraordinary women who stepped into domains, considered taboo for nuns, and made their presence felt. One of them was a marathoner! Let me add, I would indeed be happy if nuns ruled the world!

I did not know until I read this book that there were 1,30,000 women religious belonging to 300 congregations in India. No other country, including Italy, has as many sisters as India. That is quite a large number.

At Pune, I was invited to address a group of women who were undergoing training to become what they call women religious. Let me use the word “Sisters” for women religious. The trainees not only heard me with rapt attention but also asked me some questions despite the fact that while I had my sumptuous food, my talk was delaying their supper.

One cannot even imagine the Catholic Church without the presence of the sisters. With the kind of numbers they have, they should have been ruling the church and its establishments. See how Narendra Modi has been managing the nation with less than 35 percent votes in his kitty!

Gender issues in the church are not merely women’s issues. “They are human issues, moral issues and spiritual issues. We, as images of God, deserve to live in dignity. In Gandhiji’s words: ‘To call women the weaker sex is a libel, it’s men’s injustice to women”.

A Synod on “Consecrated Life” was held in Rome in 1994. There, a bishop made the startling disclosure: “In the church, 75 percent of the consecrated people are women. If there are no women, there is no Consecrated Life and no church. Hence the future of the church depends upon the response we would be giving to the women religious. If they don’t feel our support, eventually the Church will lose women too in this century”. In other words, the church will die.

In other words, providing gender justice is a matter of life and death for the church. What is the reality? Let me quote Sister Inigo SSA, former superior general, Society of the Sisters of St. Anne: “Even after 2000 years of their existence, half of the followers of Jesus are not counted. They are neither visible nor audible in the church. In India, women constitute nearly 82 percent of the religious.

Despite their large presence, the sisters face various kinds of injustice which have no explanation in a democratic society that functions on the basis of adult franchise and on the one-person-one-vote principle. Brother Philip Pinto, cfc, former superior general, Congregation of Christian Brothers, has in his brief Preface says:

“I have sat in silence as individual sisters wept through telling their stories. Enough! It’s High Time… This is now the call for action”. That is how the book got its title, It’s High Time. He continues: “Respect is obviously absent. We see highlighted the clericalism that Pope Francis is fighting against: the bullying and spiritual blackmail sisters face, the sense of entitlement that priests are taught regarding their special status and their right to be served, the patriarchal mentality that sees women as possessions and inferiors”.

It is not that the sisters are themselves not to blame. “How often the sisters are their own worst enemies! They have been brought up to treat clerics as special people and to defer to them. That needs to change. They have been trained to obey without questioning. That too needs to change”.

The book is based on a survey conducted among the major superiors of various congregations. Had ordinary sisters been included, the picture would have been clearer. For one reason or another, only one-third of the superiors took time to fill up the questionnaire that covered a whole lot of issues.

One of the immediate provocations for the study was an article L’Osservatore Romano published in 2018. The article was written by Marie Lucile Kubacki and it was titled “The Almost Free Work of Sisters”. She wrote the article based on the comments of several unnamed nuns. The article struck a chord with the sisters and the priests who were exercised over the gender-based exploitation in the Indian church too.

The survey confirmed what the article hinted at and what I observed at the Vatican in 2000 of how senior sisters were “forced” to work for nothing. Generally speaking, the sisters are wary of discussing such issues in public for they know that it can also be counterproductive.

Nonetheless, the survey reveals the fact that gender-based discrimination is a reality in the church. Figures suggest that more than sexual harassment, which does not suggest a large prevalence, it is the low esteem in which the sisters are held that should bother one and all.

When the priests undergo training at the seminaries, they see sisters working in the kitchen or doing sundry menial jobs and they get the impression that they are “mere servants”. Naturally enough, they tend to order them around even when they know that some of them are senior to them not only in age but also in rank.

One major expectation the priests have from the sisters is that they cook delicious meals for them just three times a day. They also expect them to do sundry jobs like ringing the bell early in the morning and keeping the church premises clean and tidy. They also expect them to be at their beck and call at all times.

If the sisters fail to live up to their expectation, they are harassed in hundred and one ways. The Pulpit is to spread or disseminate the word of God. It is available only to the priest. Instead of using the Pulpit for divine purposes, some of them use it to take the sisters to task. It is through the sermons that they express their displeasure.

It does not bother them that in doing so they are casting aspersions on the sisters and showing them in a poorer light. They also use sexually abusive and pejorative terms against the sisters, no matter what impact it would have on the lay public.

Institutions which the sisters have built up are taken over by a coterie of bishops and priests who think that they know best how to use church property. More often than not, the bishops are unable to control the priests even when they know that they are at fault. In the process, justice is denied. Deference is seldom shown to the sisters, who are even rebuked in public.

Even when the sisters hold high offices like principal of senior secondary schools, they are paid a pittance on the specious plea that they had taken a vow of poverty. It was unbelievable to know that some priests deny the sisters sacramental privileges like saying mass for them.

The continued use of medieval titles such as “My Lord”, “Your Lordship” “Your Excellency” together with special head dress and robes, only emphasis the institutional attachment to a bygone era, obscuring the Christ-like attitude of service.

The church needs to be sensitive. The sisters today are as educated or, in some cases, more educated than the priests. They cannot be held in suppression for long. The book has a few suggestions on how the leadership can avert a disaster by giving the sisters their due. All they want is a level-playing field in which the church truly becomes the “people of God”.