.jpg) Peter Mundackal

Peter Mundackal

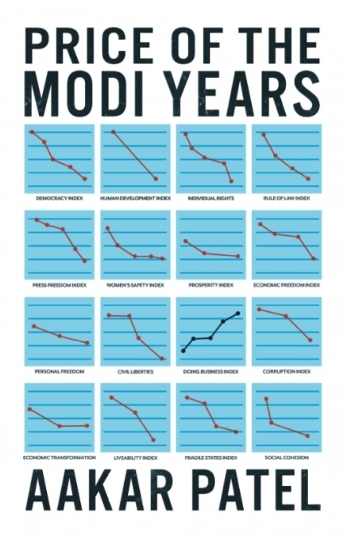

The first part of the review of “Price of the Modi Years”, which appeared in the Indian Currents of 16-22 May, dealt with the introductory chapter and first two chapters of the book. We saw that the much-hyped ‘Gujarat Model’ was inferior to several states of India, especially, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The third chapter ‘Modinomics’ deals with matters related to the Indian economy, most importantly, demonetisation.

Hitherto we knew that demonetisation was the result of an impulsive decision of Modi alone and preceded no Cabinet deliberation. But we never heard of the queer fact that Modi reportedly got the idea from one Anil Bokil, a mechanical engineer from Latur in Maharashtra, who runs an institution called Artha Kranti (economic revolution) and describes himself as an economic theorist. His thinking was: “In a country like India where 70 per cent of the population survives on just Rs 150 per day, why do we need currency notes other than Rs 100? On the Aartha Kranti website, the benefits of demonetisation which were conveyed to Modi in a meeting with him in July 2013 are listed: Terrorist and anti-national activities would be controlled; the motive for tax avoidance would be reduced; corruption would be minimised; and there would be a significant growth in employment.

Modi was naïve enough to believe these and that is why he went ahead and cancelled 86% of the currency circulating in Rs.1000 and Rs.500 notes, in four hours at midnight on 8 November 2016. Strangely, he also announced the introduction of a Rs 2000 note and new Rs.500 note. Any black money held in four Rs 500 notes could now be held in one Rs 2000 note! “Modi’s demonetisation exercise,” says Aakar, “had all the eccentricity of the Bokil plan without any real change in high value currency notes as Bokil had envisaged.”

Demonetisation could not achieve any of the declared objectives. It could not reduce black money, as it came to light that there was hardly any black money in circulation, since 99% of the old currency came back, ending another myth about demonetisation. It confirmed the presupposition that most of the black money was held in real estate and in gold. I remember Modi’s promise in 2014 to bring back all the money stashed abroad and to put Rs 15 lakh in the account of each one of us! Amit Shah glibly told Supria Sule in Parliament that the promise was a ‘jumla’!

Corruption did not come down. “On Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index of 2015, India was ranked 76. In 2016, India fell to 79. In 2019, it fell further to 80. In 2021, it fell to 86. Even the perception on corruption had not improved.” On the terrorism front too, the story is the same. Fatalities in Kashmir rose after demonetisation – “from 267 in 2016 to 357 the next year, to 452 in 2018 and 283 in 2019. In 2020, they were 321”.

Aakar Patel then reveals how the Reserve Bank of India, the body which is actually empowered to demonetise the currency, was made to own up all the drama, how Raghuram Rajan, the RBI Governor as well as his successor, Urjit Patel, had to leave before completing their terms, etc. Aakar goes on to list the adverse effects on the Indian economy, like the decline in real estate business, fall in the farm income and wages, contraction in the factory investment, fall in the share of manufacturing in the GDP, fall in exports etc, some of which, in fact, are still lingering.

By the time the first wave of Covid ended, India’s 10 crore middle class was smaller by 3.2 crore people. “The number of poor Indians (earning $ 2 or less per day), went up by 7.5 crore in 2020”, as per the website pewresearch.org. Thus, Modi undid the entire work of the previous government on social welfare and put crores of Indians through trauma. ‘The Economic Times’ of 19 March 2018 reported that “the really rich fled India. Between 2014 and 2018, a total of 2300 dollar millionaires (meaning Indians worth Rs 7 crore or more) left India, the highest number of millionaire migration out of a nation in the third world”. All this happened before Covid.

What about the poor? Their main hope was MGNREGA, a scheme, conceived and introduced by UPA and which Modi had earlier made fun of. “From 1.84 crore households asking for MGNERGA work in 2019, the number rose to 3.15 crore in 2020”.

Aravind Panagaria, economist and professor at Columbia University, who used to be an admirer of Modi earlier, turned a critic and left the position as deputy head of NITI Ayog. “He flitted between adoration and deification of Modi one day and the next day producing a paper, the key thesis of which was that India’s best growth years were actually 2003 to 2014”, i.e. the entire UPA term. This was in conformity with what OXFAM had reported on 12 July 2019, that during the two terms of Manmohan Singh’s Government from 2004 to 2014, 271 million (27 crores) Indians were pulled out of poverty.

Aakar makes a revealing statement about how Modi viewed advices, economic or political, which he received. “Think Tank (NITI Ayog) members on leaving have said that the Prime Minister was receptive to ideas that were in conformity with what he wanted, but uninterested in the rest……” “The finance ministry and foreign ministry,” Aakar continues, “are managed at the top by individuals who find it difficult to say no to Modi, which is because they have no authority of their own (which they do not) or because they are opportunists, who don’t care about the consequences. Or both.”

Modi’s economic policies led to increasing inequality. In a leading article ‘The Economist’ reported that “Gautam Adani’s net worth went up by 750% in 2020. Mukesh Ambani’s went up by 350% in that year – the year in which India’s GDP shrank and crores of people became destitute”. ‘The Hindu’ reported that “when the world added 3 billionaires every two days, India added one every week”.

Of the chapters that follow, I should skip a few and dwell on the 6th chapter “Bad Muslim”, because of its sickening relevance to the increasing polarisation of communities that we are witnessing for a few years. Aakar Patel has made a meticulous study of the crimes (which he nick-named as ‘beef lynching’), committed against Muslims by the now notorious cow vigilantes, during the 5 years from 2015 to 2019, and has listed the same, year-wise and date-wise, with names and dates of the publications in which these were reported. Particulars like nature and extent of the crime, names of individuals – 99.9% Muslims – who were murdered or injured, nature of their purported offence, most of which appear to be trading in buffalo meat (not cow meat).

At least 60 men, mostly Muslim youth were murdered and similar number were severely injured. There were also a few cases of raping women, on suspicion of eating of beef. The litany of these incidents makes distressful reading. These incidents total 90: 2015 – 11, 2016 – 26, 2017 – 28, 2018 – 16 and 2019 – 9. State-wise, UP tops the list with 17 incidents, followed by Haryana (13), Jharkhand (10), Karnataka (9), Rajasthan (8), Gujarat (7), Assam, Bihar and Maharashtra 3 each, Telangana (2) and the rest 1 each. Some typical cases are quoted below, which are illustrative but not exhaustive:

*It occurred on 28 September 2015 at Dadri in UP. Mohammed Akhlaq, 52, was killed after being lynched by a mob that broke into his house and accused him of cow slaughter. Akhlaq’s son, Danish, was also assaulted but survived. This was the famous case that brought beef lynching to national attention. Five years after the murder, the government began a fast-track court trial.

*It occurred on 27 March 2016 at Kurukshetra, Haryana. Mustain Abbas was murdered after being lynched by four men for buying a bull to plough his fields. No arrests were made. After the family moved the High Court, it ordered the immediate transfer of the Kurukshetra district magistrate, the superintendent of police, the deputy superintendent of police and the station house officer of Shahbad police station. The Supreme Court stayed the decision.

*It occurred on 5 March 2018 in Gandhinagar, Gujarat. 32-year-old Farnaz Sayed was killed and mother Roshnabiwi Syed was wounded when they were out grazing their cattle. Roshnabiwi’s fingers were chopped off while Farnaz was hit on the head, who later died.

The chapter “Good Governance” is notable for Modi’s bombastic claim on 29 April 2018: “I am delighted that every single village of India now had access to electricity.” This is what Aakar says about Modi’s claim: “The problem with calling this Modi’s village electrification was that it was not true for a couple of reasons. Firstly, while average villages thus electrified were 6,000 per year under Modi, they had been 10,000 per year under Manmohan Singh in his second term, and over 12,000 per year in his first”. I am reminded of a blunt statement by Rajmohan Gandhi, the great grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, in an article “Dear Leader” in The Indian Express equating Trump with Modi: “Prime Minister Modi has thick skin. He can build the world’s tallest statue for Sardar Patel one day and later calmly agree that his own name should replace that of Patel for the prestigious stadium”!

Of the remaining chapters, “Their Lordships” deals with the conduct of some judges and Modi’s role in shielding some judges like Ranjan Gogoi, and Arun Mishra who had liberally praised Modi at a meeting on 22 February 2020. He had delivered a few judgements in some cases in which Modi had a lot of interest. In June 2021, he was rewarded with a three-year term as the chairman of the National Human Rights Commission. He is the first non-chief justice appointed to the position after a change Modi made in the rules in 2019.

The chapter enables us to have a peep into the noble role played by a few principled advocates like Dushyant Dave and Prashant Bhushan.

Overall, ‘Price of the Modi Years’ takes a close look at the present government at the Centre. It gives a better insight into the hitherto little-known facts about the Modi regime, and is worth reading.