A. J. Philip

A. J. Philip

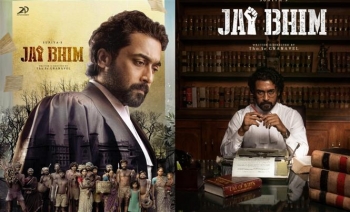

The problem with watching a movie on over-the-top (OTT) platforms like Amazon, Netflix and Hotstar is that you are tempted to watch it in parts, sometimes over several days. I saw T. J. Gnanavel’s film Jai Bhim (Malayalam) in one go, though I began watching it late in the evening. There was not a moment when I got bored.

I am unable to recall when I had this kind of an experience. Was it because the film depicted a real incident that happened three decades ago in Tamil Nadu? Was it because the story was so gripping and the acting and direction superb? Whatever be the case, the film shook me. The performance of the chief protagonists, advocate Chandru, played by Suriya, and victims Senggeni, played by Lijomole Jose, and Rajakannu, played by K Manikantan, was outstanding.

To be frank, the story is very ordinary. A poor Irular snake-catcher, who dotes on his wife and daughter, is arrested on the suspicion that he stole the jewellery of a politically well-connected landlord. Since he belongs to that caste, his word has no value and he and his relatives are thrashed at the police station to extract a confession.

Rajakannu, who is subjected to the worst kinds of third-degree methods, succumbs to the agony and torture. The police spread the story that he and two others have escaped from the police station. I have myself reported worse cases.

A massacre happened in Central Bihar in the eighties when a Dalit man gave a fashionable name to his daughter. Unfortunately for him, the landlord’s granddaughter was also called by the same name. How dare an Untouchable appropriate a name reserved for the upper castes?

Of course, they can have such names provided the pronunciation and spellings are different like Kovind, distinct from Govind.

There was a far more poignant story reported from Tamil Nadu where a father and son duo were tortured and killed in the police station because they dared to question the local police, despite being Dalits. The murders would have been written off but for an English-speaking girl who narrated the story in a video, published on social media. Finally, the police had to arrest the murderers among them.

A Dalit Christian had to remain in jail for three years because he protested against the practice of bringing a rich man’s dog to defecate in front of his house. He protested and the man managed to file a false POSCO case against him by his granddaughter.

The court found that he was innocent but by then he had spent Rs 2 lakh, an enormous sum for him, in fighting the case and three years in jail. The Indian Express reported that he spent his time in jail reciting the scriptural verses he knew by heart. I read this story a few months ago. In comparison, the Jai Bhim story is pedestrian, if I may say so.

However, what makes the story so touching is that Senggeni, despite all the beatings she suffered at the hands of the police, is not prepared to say quits and is “ready to go anywhere”, despite her advanced stage of pregnancy to ensure that the killers in uniform are duly punished.

One of the most dramatic moments in the film is when she flatly refuses the Tamil Nadu police chief’s promise to get for her a good sum of money if she withdraws the case against the policemen.

The film ends with the court order under which she is given Rs 3 lakh as compensation and allotment of two-and-a-half cents of land in the heart of the village where generations of Irulars lived without any legal entitlements.

She is even seen moving into a newly built, white-washed house made of brick and mortar. I titled this article, “Portrayal of reality”.

How did the original case end? I listened to an interview Lijomol Jose gave to a television channel in which she confessed that though she wanted to meet Parvathy, the Irular woman who fought against the police, she could not. She would have loved to meet her and imitate her mannerisms. I was also curious to know about Parvathy.

Fortunately, I was able to watch a long interview she gave to a lady journalist. Parvathy did not even know that a film was produced on her and the film, released on the same day in several South Indian and Hindi languages, had become a super hit. Amazon bought the rights of the film, reportedly, for Rs 100 crore!

Parvathi’s condition is pathetic. The land given to her by the government on the High Court’s order was uninhabitable. She built her present thatched hut which can be accessed only by crossing a stream of dirty water in another part of the village. She has no toilet of her own. Nor does she have a proper kitchen. She uses a public toilet at quite a distance from her house, which is in many ways like Senggeni’s house, where a wall collapsed on a rainy night soon after the couple made love.

The compensation she received was distributed among all the victims. In short, her condition remains much the same. She still retains her sense of justice and demeanour and speaks like an accomplisher.

She is no longer the one who meekly told the lawyer that she was illiterate and could not, therefore, sign. Parvathy is today an empowered lady.

Come to think of it, Jai Bhim would have been just a documentary, seen by a few at documentary festivals, but for Tamil actor Suriya’s involvement in the film both as an actor and a producer. His role is modelled after Justice K. Chandru, a former judge of the Madras High Court, who accepted Parvathy’s brief while he was a lawyer in the nineties.

I was very happy to watch a video in which the retired judge was interviewed. He gave some details of the case which showed that the original story was greater than the celluloid one.

For instance, when the police were cornered by him in the court, they tried to bribe Parvathy with Rs 1 lakh, a huge sum for an Irular woman. Thereafter, he himself was approached by the police with a bribe.

The local police also used strong-arm methods to browbeat the investigation ordered by the Madras High Court. They even resorted to arson. However, he stood his ground and saw to it that justice was finally done in the case.

Meanwhile, I read an article, written by a journalist-turned-novelist, in which he picks holes in the film. He finds the portrayal of casteism in the film objectionable. He says the film does not say why Chandru is pro-poor, pro-Dalit and why Lijomole Jose had to be painted black and oily.

The fact is that caste and casteism are realities. Just as only the wearer knows where the shoe pinches, only a Dalit knows when he feels hurt. I as a journalist or as a privileged person in society can empathise with a Dalit but I cannot feel like a Dalit. If I say that I can feel like a Dalit, it would be boastful, to say the least.

Suriya is depicted as an admirer of Ambedkar. Anyone who knows the father of the Constitution and has read his works would easily become his admirer. In the film, no attempt has been made to straitjacket the characters into Irulars or non-Irulars. I do not know what caste Justice Chandru or Suriya belong to. It is unimportant.

In the film, there is one character Mythra, played by Rajisha Vijayan, a teacher tasked with teaching the Irulars, who plays a major role. She is with Senggeni at every turn of the story. In fact, it was she who introduces her to Chandru, speaks on her behalf and takes the advocate on his own investigation of the case.

No black paint or oil was used on her. Jai Bhim is not a film by Dalits, of Dalits and for Dalits.

I do not know how many would have noticed the indebtedness the film maker expresses to two judges — Late Justice P.S. Mishra and Justice Sivraj Patil. In the film, the habeas corpus case filed by Senggeni is heard by a two-member Bench. The judges are not identified. I can only presume that the case was originally heard and decided by the two judges whose names I mentioned.

Justice Chandru, who retired as a judge of the Madras High Court, gave many verdicts under which segregation on the basis of caste at burial grounds was abolished and women were allowed to become temple priests. In the interview I mentioned, he paid handsome tributes to the late Justice Prabha Shankar Mishra from Bihar, who showed real courage when he accepted the habeas corpus application filed by Parvathy. He listed several other cases in which Mishra gave pathbreaking verdicts.

Justice Mishra went on to become Chief Justice of the Andhra Pradesh and Calcutta High Courts. Need I mention that Mishra, who depended on a local police officer, instead of the CBI, to punish the guilty policemen, was a Brahmin? Justice should have no religion or colour.

The large courtroom where much of the action in the film happens is modelled after the Chief Justice’s courtroom. There, on the wall facing the judges are two portraits. One of them is that of Justice VR Krishna Iyer. Why are those portraits placed there?

The two judges happen to be Justice Chandru’s role models in his career. In the late sixties, Justice Iyer visited Catholicate College, Pathanamthitta, to inaugurate the college union. I was hypnotised by his speech. I read the verdict he gave on Indira Gandhi’s petition challenging the verdict of the Allahabad High Court unseating her from Parliament several times. Later, I had a long interview with him at Patna. As luck would have it, I also edited his articles while I was with the Hindustan Times.

Justice Chandru is not the only one to rate Iyer high. In his autobiography Before Memory Fades, the well-known lawyer Fali S. Nariman, describes him as one of the greatest judges of India, although he never became the Chief Justice of India.

Jai Bhim should not be seen through the prism of caste. I have noticed that those who claim to be above casteism are often the worst practitioners of casteism. As everyone knows, Jai Bhim is a slogan used by the followers of Dr BR Ambedkar. What they foresee is not subjugation of any caste but letting everyone play his role in the development of the country and also enjoy a share of the national property. Is that the case?

Parvathy still lives in a house, easily accessible by centipedes and snakes, despite winning a much-celebrated legal battle. The condition of her compatriots is no better, though 75 years have passed since India attained Independence. Jai Bhim is not just about lock-up murder. It is also about denial of voting rights, educational opportunities, proper wages and a level-playing field.

The police continue to be an instrument of oppression despite the Delhi Police’s motto of Shanti Seva Nyaya (Peace, Service, Justice). Despite so many laws to protect the interests of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, they are subjected to atrocities even when they do certain traditional jobs like skinning animals.

Those who speak against reservation of jobs for SCs and STs have no objection while reserving almost all the jobs of janitors, drainage cleaners and sweepers to those very persons.

They want the Untouchables to remain on the fringes of society. Fortunately, there are Senggenis and Chandrus who will not let that situation continue for long. That is the message of Jai Bhim.

ajphilip@gmail.com