.png) John Dayal

John Dayal

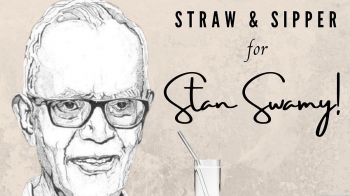

A little plastic straw, much like you'd get with your fresh tender coconut or cold drink at a roadside vendor's kiosk, has focused world’s attention not just on the vagaries of the law of the land and its courts, but even more on the conditions in the prisons in India.

It took several weeks for 83-year-old Jesuit Stan Swamy -- in prison as a mere suspect in a trumped-up conspiracy called the Bhima-Koregaon Case, not yet an undertrial, and certainly not a convict -- to get the plastic straw he needs to take a sip of water or tea because his Parkinson’s disease afflicted hands can barely hold the cup.

It has taken a few years and many appeals in courts for Delhi University Associate professor G Saibaba, a wheelchair-bound paraplegic who needs the assistance of two fellow prisoners to go to the toilet, seeking treatment he needs if he is not to die in his cell. His plaintive cry has gone unheard. He is an accused in a different conspiracy, not for triggering off a bomb blast, but for being an intellectual supporter of political militants opposed to the state.

A third activist, Gautam Navlakha, now in jail, also in the Koregaon case, has been denied a pair of spectacles which he wore when he was arrested, but have been taken away from him by someone in prison. He is all but blind without them. A pair of glasses sent by his family have not been received by the jail authorities.

These three cases beg for answer of the State, but this is about the situation in Indian jails where people on the verge of death, doddering octogenarians and youth arrested on mere suspicion because they professed a certain religious, caste or ethnic identity, serve more than the sentence they would have merited if they were indeed guilty of the crimes for which they are now in custody.

Government is tardy with revealing data regarding the condition of prisons. The only official data is released by the National Crime Research Bureau. Despite the internet, digitizing of all police stations and courts, the recourse to artificial intelligence and number-crunching computers, the 2019 Prison Statistics India gives the figures of 2018. We will always be two years behind in information, as a default situation.

In 2018, therefore, we are told there were 1,350 prisons, up from 1,339 the previous year. These 1,350 prions had a capacity of holding -- for want of another term -- 4,03,739 human beings. But they held 4,78,600 persons, almost 20% more than their capacity. The big prisons in major towns of the bigger states had actually a much higher density of inmates.

The 1,350 prisons in the country consist of 617 Sub Jails, 410 District Jails, 144 Central Jails, 86 Open Jails, 41 Special Jails, 31 Women Jails, 19 Borstal Schools and 2 other jails. The highest number of jails was reported in Rajasthan (144) followed by Tamil Nadu (141), Madhya Pradesh (131), Andhra Pradesh (106), Karnataka (104) and Odisha (91). These Six (6) States together cover 53.11 % of total jails in the country as on 31st December, 2019, according to the Bureau's Executive summary of the data. Delhi has 14 Central jails, the highest in the country. Uttar Pradesh, India's largest state, has 62 district jails.

Just 15 States/UTs have jails for women prisoners -- a total of 31 with a total capacity of 6,511. Of the 4,78,600 prisoners, 4,58,687 were men and 19,913 were women prisoners. The women's jails are even more overcrowded, unless states are not revealing that women prisoners may have been kept in some quarter of the male jail systems.

The national capital, Delhi, has the highest occupancy rate (174.9%) followed by Uttar Pradesh (167.9%) and Uttarakhand (159.0%) as on 31st December, 2019.

The more critical data is about undertrials, who have been in jail sometimes for a decade, if not more. Most of them are poor, Dalits or Muslims, far exceeding their presence in the general national population. There are 3,30,487 undertrial persons among the 4,78,600 inmates. The Bureau said that of the total inmates in prisons, the actual convicts numbered 1,44,125; there were 3,30,487 undertrials and 3,223 "detenus", apart from 765 inmates who could not be classified in any of the official categories.

The situation of the Undertrial Prisoners merits attention. The Bureau admits that the number of undertrial prisoners has increased from 3,23,537 in 2018 to 3,30,487 in 2019. Almost half of them are in district jails and about 36 % in central prisons.

The number of detenus has increased from 2,384 in 2018 to 3,223 in 2019 -- a 35.19% increase. Tamil Nadu has reported the maximum number of detenus (38.5%, 1,240) followed by Gujarat (21.7%, 698) and Jammu & Kashmir (12.5%, 404) at the end of 2019.

I do not know I should describe it as official compassion or not, but there were 1,543 women prisoners with 1,779 children as on 31st December, 2019. Of these, 1,212 women were undertrial prisoners who were accompanied by 1,409 children and 325 convicted prisoners who were with 363 children. Some of these children may well have been born in jail.

Among the 3,30,487 undertrial prisoners, around 74.08 % were confined for a period up to 1 year (2,44,841 prisoners). There were 44,135 undertrial prisoners (13.35%) confined for 1 to 2 years. But 5,011 undertrial prisoners (accounting for 1.52% of total undertrial prisoners) were confined for more than 5 years.

The grim data is on deaths and illness in prisons. In 2019, there were 1,845 deaths, most described as "natural', but as many as 165 were called "unnatural deaths”, a term which admittedly includes suicide or murder. Among the 165 unnatural deaths, 116 had committed suicide, 20 died in accidents, 10 were murdered by inmates and one died due to assault by outside elements during 2019. For a total of 66 deaths, the cause of the death is yet to be known.

Just as closing paragraph, 468 prisoners escaped captivity but 231 were caught again. As many as 20 jail-breaks occurred during 2019.

The saving grace? Unlike in some other countries, India has not privatised or corporatized the prison system. Not yet.