A. J. Philip

A. J. Philip

I was born six years after India became an independent nation and three years after it became a Republic with a Constitution that incorporates the best in Constitutional thinking the world over. Few new-born countries have invested as much time and thought in the drafting of the Constitution as India. The debates in the Constituent Assembly, which are properly documented and recorded, bear proof of what I stated.

My earliest memory is that of my Aasan (teacher) initiating me into learning on the Vidyarambham (beginning of education) day by helping me write Om Hari Sri Ganapataye Namah (Salutations to Hari (Lord Vishnu), Shree (the Goddess of prosperity), and Lord Ganapathy) on a large plate of raw rice that was packed and given to him besides the Dakshina (offertory) that I was asked to give in a betel leaf with a fresh areca nut.

Asan lived on the other side of the Achenkovil river, the only large river in Kerala that has not been tamed, and which is a tributary of the sacred Pampa. He had a nursery school in the heart of Pathanamthitta town where Radha Talkies came up later. The school was just a small shed with a thatched roof. The only furniture was a stool on which Aasan sat occasionally.

We children brought our own mats to sit on the sand floor. Aasan used palm leaves to write the Malayalam alphabet. He used an iron writing instrument for this purpose. His handwriting was rounded and very beautiful. I was not a bad student. The school was about a kilometre from my house. Aasan took me there every day. Other children were jealous of my proximity to him.

A student’s competence could be measured by the number of palm leaves he had. A new leaf with new words and sentences were given only after the text on the previous leaves had been learnt by heart. I had a sizable collection of leaves. My eternal regret is that I never kept the leaves with me as I was admitted to the Government Primary School, bang opposite the Pathanamthitta Taluk office.

I should normally have been admitted to the Marthoma School. Why my parents chose the government school was because we had a neighbour who taught there. She had two sons, one of whom was of my age. I would accompany the teacher and her sons to the school. My parents were free of the bother of my safety.

Most of my classmates were Muslims and they were very poor. They did not wear any shirts. All they wore was a towel around their waist. However, I felt jealous of them when at meal time, they were given a large glass of milk, made of milk powder that came courtesy the US government. They were also given Upma, made of imported material.

“Rich” and upper caste children were exempted from the mid-day meal scheme. I had to make do with whatever tiffin that my mother would put in the school bag. I could never taste the milk and Upma. I presume they were good as I had seen teachers having them to their heart’s content in the Teachers Room. I lamented that I was considered “rich”!

Poverty was a reality. In my neighbourhood, people subsisted mainly on dry tapioca. They could not always afford a side dish like the sardine curry. My immediate neighbour was our landlord, who got Rs 10 as monthly rent from us. He had a large family to support. He would go fishing in the Achenkovil. He would bring home some tiny fish after he had sold the main catches.

His wife always complained that he was miserly. They were tired of eating tapioca. She would once in a fortnight or so make dosa dough and make dosa in our kitchen. The children would come home surreptitiously and eat the dosa. She did so because her husband would ask her from where she managed to get rice and pulses to make the dough.

The children were good in studies. They seldom had rice. I saw them making a powder of tamarind seeds and making a dish of it. They used a little jaggery to make the dish tastier. I could never taste it as my mother said it was not good for the stomach. I wondered how they could eat without their stomach getting upset.

Rice was a luxury only a few could afford those days. The poor depended on other cheap substitutes. Around the time I completed my primary education, we shifted to Thekkepuram at Ranny. We had a perennial stream flowing in front of our house. I knew some children from the Paraya community.

I did not know at that time that the Parayas were the lowest in the caste structure. They were very poor. They had big bellies and both boys and girls wore a piece of the fibrous material from the Areca nut tree to cover their nakedness. In retrospect, I wonder why nobody gave them clothes to wear. There were enough rich people in the village.

I found the children very adventurous. They were not afraid of the snakes in the stream. I would follow them as they looked for crabs. Eventually, they would catch some. I did not know how they were cooked or eaten till many decades later my relative took me to an upmarket restaurant in Toronto where crabs and octopus were served.

The children’s parents would occasionally visit my grandfather for permission to pluck a jackfruit from our tree. He would get one plucked for ourselves too. Our house too had a thatched roof. Every year the palm leaves with which the roof was thatched had to be changed.

It was a grand occasion in the village. Neighbours and friends volunteered to do the job. In return they had a feast, served on plantain leaves. All the crab-catching children too could have liberal helpings of payasam, a sweet dish served at the end of the meal.

School education was free till Class VIII. Most girls dropped out of school at that stage. They would remain at home till they are married off. The good-looking ones had better chances of an early marriage while the others had to wait till someone took pity on them and agreed to a marriage. One of my close friends who was good in studies dropped out at that stage, as he did not want to be a burden to his widowed mother. He started working as a labourer. He would borrow books from me to read.

The monthly fee in Class IX and X was Rs 6. It was a big sum those days. The daily wage of a labourer was Rs 3. That means the fees of a child was worth two days’ wages. Today the daily wage is about Rs 1000. That means a monthly fee of Rs 2000! There was a fine of 25 paise if the fee was not paid before the 10th day of the month. The fine would double to 50 paise by the end of the month.

It did not bother the government that a poor boy or girl could not pay fees in time because he/she had no money. How could such students be expected to pay a fine too? I have seen students, especially girls, stop coming to school after their names are struck off the register for non-payment of fees.

Though I remember India’s war with China in 1962, I do not have any memories of how it impacted life in our part of Kerala. All I remember is that I took part in a rally in which we denounced the half-nosed Chou-en-Lai. We had no idea of who Mao was at that time.

However, I have vivid memories of the war with Pakistan in 1965. There was scarcity of food material at Ranny and nearby places. Rice was not available in any of the shops. There were also reports of looting of rice from trucks returning from the Food Corporation of India godown. It was a period when famine stared us in the face.

We had a relative who owned a wholesale ration depot. He managed to send us a sack of rice with which we managed a month. That was the time when tamarind seeds were once again in demand. People found substitutes for rice and tapioca. I remember the kind of relief the people of my village felt when the war ended.

It was the need to feed his family of mother, two brothers and one sister that forced my father to enrol himself in the Army, where he was posted in the Burmese sector during the Second World War. I remember these experiences whenever people talk loosely about a war as the ultimate solution for border disputes.

As children, we looked forward to celebrating Independence Day and Republic Day at the school. One attraction were the lozenges distributed free among the children by the school authorities. The lozenges would not have cost more than 5 paise per child but the happiness they gave us was immeasurable. No, we could not afford to have flags at home.

We had two big flags at home. My father would keep them safely. They were hoisted on our buses on Independence Day and the Republic Day.

India was a poor country and poverty was visible everywhere. My dream was to buy a Raleigh bicycle but that never happened. The cycle was made in England. We had a teacher who owned a Raleigh. Soon the market was flooded with Indian brands like Hercules, Norton, Phillips and Hero.

It took many years for electricity to reach my village. Our neighbour first got it by paying for several poles to bring electricity to Thekkepuram from Manniram where the Marthoma Church has a diocese office now. That is when I developed the habit of sitting near my neighbour’s house in the evening to listen to the Malayalam songs broadcast by Akashvani.

Those days transistor radio was the privilege of a soldier, who would bring it the first time he visited home after training. Most of them took the transistor back. Even if it was left at home, it would seldom be played to save the battery.

After 10th, only few could think of going to a college. By then colleges had come up at Pathanamthitta and Kozhencherry. The rich ones would send their wards to places like Ernakulam and Thiruvanthapuram. The opening of a college at Ranny was a godsend for many.

One of my friends was in the first batch. He became a doctor and settled himself in London after a nurse kicked up a shindy over his alleged affair. Another friend, who initiated me into Malayalam literature by forcing me to read MT Vasudevan Nair’s Nalukettu, got a job in the Malayalam department of Saint Thomas College, Ranny.

By then, we had gone back to Pathanamthitta where Radha Talkies stood where my nursery school once stood. Religiosity had reached such heights that the Orthodox Church bought half a cent of land at Pathanamthitta Junction for over Rs 1 lakh, a princely sum in the late-sixties, to erect a cross. Cross cultivation had become rampant.

On a visit to my alma mater recently, the Principal told me that Christians of the area were no longer interested in studying there. They prefer colleges in Bengaluru, if they can’t afford to send their wards to London and Toronto. Kerala has changed and so has India.

The stark poverty that I found in Bihar where I lived for 10 years is no longer there. Nobody remains naked for want of clothes, though I was shocked to find an acquaintance’s wife wearing an old blouse, torn multiple times in the first year of the 21st century.

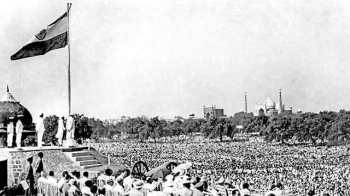

India has come a long way since the time the Birlas bought an antiquated car factory and brought it piece by piece to Kolkata to make and sell Ambassador cars. Today, the first indigenously made aircraft carrier is ready to be commissioned in the Indian Navy. We, as a nation, have a long way to go. Our journey began on August 15, 1947, not in 2014 as some would claim, and we will become a great nation if our progress is not derailed in the name of religion and caste. I wish all my readers a very happy and prosperous Independence Day.

ajphilip@gmail.com